The Rise of the Far-Right: Hindu Nationalism in India and Aotearoa

“Nationalism is inseparable from the desire for power” -George Orwell, “Notes on Nationalism”

Divide and conquer. This has been one of the most powerful remnants of colonialism’s bloody history. And it is this legacy that I contend is at the heart of one of the most controversial administrations of India.

Interference with citizenship is a dangerous game to play. Indian Prime Minister Nahendra Modi, of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), is a polarising political figure in his native country, but is well supported by citizens who believe that he is the answer to many economic and political challenges his voters face. Criticism of Modi reached fever pitch regarding two key decisions in his administration; rushed revocation of the special administrative status of Kashmir and the subsequent media blackout, and the most recent changes being the Citizenship Amendment Act 2019 (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC). At present, reports from Al-Jazeera and Amnesty International India detail increasingly violent attempts by mobs to suppress protests against the CAA and NRC.

The CAA states that migrants and asylum seekers of Hindu, Christian, Buddhist, Jain, Sikh and Parsi descent may apply for citizenship. There is a key exclusion to this legislation that neglects the long history of Rohingya and Tamil refugees wishing to seek asylum and their present experience of persecution. The legislation, at initial glance, appears to be ‘positive action’, but is in a sense, an omission, preventing something from happening. In this case, it is the prevention of legal legitimacy of historically established narratives of Muslim refugees. Kaushik Deka of India Today has reported that the reasoning of BJP are the beliefs that Muslim refugees may be a risk to security, and a nationalist motive that Islam is not compatible with the identity of India.

I argue that this is influenced by the playbook of anti-refugee policy of the West, with CAA not presented as a bill to help and support asylum seekers, but rather to define India as a ‘Hindu Nation’. This is akin to the Western far-right idea that nations may be unchanging entities of a singular ‘Christian’ identity. This calls to mind the irresponsibility of Executive Order 13769 of Trump’s United States, with proponents of the ‘Muslim Ban’ believing in the idea of an America that is somehow ‘incompatible’ with the foreign values of Muslims. This unchanging view of nations often neglects social and political changes that affect the fact that nations are socially constructed to begin with.

Fuelled by a fear and distrust of ‘illegal immigrants’, the NRC was hailed as a ‘solution’ to register citizens. The controversy of NRC works hand in hand with that of the CAA; whoever is alleged to be ‘illegal’, may become stateless. Statelessness severely limits access to land title, education, access to social services and ability to obtain a passport for example. To enforce statelessness is a form of institutional violence, a form of violence which prevents people from having their basic needs met in society and a prevention from excelling and living a life free of hardship and rights violations. With CAA on the horizon and with Muslim refugees unable to apply to be citizens, there is the very real chance that discrimination in India will grow to reach bureaucratic exclusion.

February 17, 2019; 10:38AM

Aotearoa is home to a large Indian diaspora community. As such, issues of Indian politics are to impact a significant amount of those living in Aotearoa. Indeed, information readily available from the Twitter of a self-proclaimed South Asian Nationalist group* indicates the presence of National MP Kanwaijit Singh Bakshi at a vigil, showing the presence of a passionate and noticeable group apparently linked to BJP, in New Zealand.

Presence for and against aspects of Nahendra Modi’s administration have been present throughout Auckland’s summer. What do these events mean? And how do we place them in the complex modern history of India?

Gujarat, the epicentre of Modi’s support, claims to have benefited economically from Modi. Measuring economic development is highly subjective as a measure of success and justifying any regime. Gujarat has exhibited GDP growth, but has noticeable numbers of child mortality and child malnutrition rates according to 2017 data from the BBC. It is clear then, that economic development may not reach everyone, and regardless, why should unequal economic development take priority over the rights of potentially millions in India?

BJP and their supporters were the focal point of the 2004 documentary, Final Solution by Rakesh Sharma. Like the documentary’s namesake, the situation in India raises comparisons to legitimised institutional violence. It is a common suggestion in ethnic violence scholarship that BJP may have been complicit in ethnic riots. Academics Paul Brass and Steven Wilkinson examine patterns in the 2000s, including provocative public appearances, media emphasis on specifically Muslim violence and creating a sense of necessity in uniting the Hindu vote and populace. These have been replicated in today’s India.

In addition, researcher Ward Berenschot of Leiden University carried out a 2009 comparative study of a neighbourhood with frequent episodes of ethnic violence compared to a peaceful one. The difference? BJP had a significantly higher amount of victories in districts where violence had been encouraged. Techniques included the recruitment of poorer or demoralised individuals to join their cause and having support from police. Modi, now as Prime Minister of India, unmarred by controversy of abetting 2002 ethnic riots, fears remain in India that he is encouraging similar feelings of justified rage.

Modi’s platform upholds an ideology of Hindutva, Hindu Nationalism. The word and ideology was formalised in the 1920s, with the view that the Indian identity is inherently Hindu. This ideology persisted as India sought independence.

Hindutva has been criticised for its historical roots, as B.S Moonje, their leader, was inspired by the ideology of Mussolini in 1931. There is then, a clear similarity in a nationalist idea of a nation that excludes others and willing to use violence to do so. Hindutva has also been criticised by civil society organisation Sadhana, for being incompatible with core dogma of Hinduism, including oneness (ekatva) and nonviolence (ahimsa). Indeed, undermining the dignity of other groups seems a far cry from ideals of goodness and truth. Thus, we may feel a moral duty to think about how Western waves of the far right may be engulfing Asia for the worst.

It is time to speak out. Following the Christchurch tragedy, we must remember that Aotearoa has a unique and necessary role to play in mending a sense of unity against Islamophobia.

Zooni (Name has been changed to protect her identity) is an activist leader in the Kashmiri community and is well aware of social changes to Indian communities.

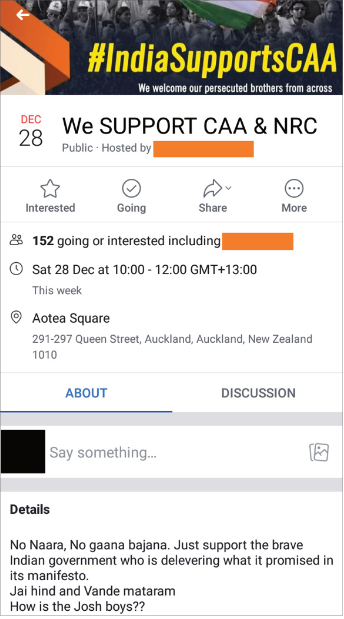

Zooni raises that there are active attempts to replicate pro-CAA rallies in Auckland, such as a deleted event of over 100 respondents. Zooni says that “hundreds of people protesting others who have lived in the country and challenging their legal legitimacy is hateful”.

She believes that recent developments regarding Kashmir, the CAA and NRC are “100% connected to Islamophobia”. Zooni claims that “hate speech has political currency” in India, starting from powerful individuals, then repeated by those in her own community in New Zealand who have attempted to hold events in support of CAA.

Zooni’s mother grew up in New Delhi and previously spoke of inclusion and celebration of festivals regardless of faith, now the situation is described as being “the opposite of what it was before”.

“As a Kiwi-Kashmiri, more than ever, I have never felt so personally affected and it’s important as a country to further our responsibility to see what we can do. There should be some talk in parliament here.” Zooni continues to speak of an experience of an attempt to hold a symposium regarding Kashmir and Human Rights with the support of local MPs, only to receive pressure from the Indian Embassy to shut it down. This was at the suggestion that ‘taking a stance’ would affect trade, which raises the question as to why these interests should override human rights, and whether it would continue to do so regarding CAA and NRC.

As we watch footage of protestors met with extrajudicial force, or people vilifying protestors for being ‘violent’, I raise the convention of international human rights that no one should be subject to arbitrary force or extrajudicial punishment, that nothing can justify this. With any vision of grandeur, utopia and national strength, there will always be those who are exempt from this image and violently so. As we have watched in Myanmar, meddling with citizenship is almost always the next step to allow dehumanisation and ethnic cleansing, if not from the state, from the understandings of ordinary citizens. For this reason, Aotearoa may be watching, but only time will tell as to how much longer we can be bystanders.

*Writer has chosen not to name the group as to not grant them notoriety.