Opinion: Sexist Treatment of Women in Politics

Alex Sims discusses the barriers women face in their political careers.

In 1893 New Zealand was the first country in the world to give women the right to vote, making history. But how far have we really come today, in terms of the treatment of women in the political sphere? The percentage of women members of parliament (MPs) hovered around 30% since 1996, reaching a new high of 38.4% in last year’s election. Many female politicians still feel that they face casual sexism in the political sphere.

National MP Judith Collins has stated that women in politics continue to be critiqued based on their physical appearance and age, much more frequently than male MPs. Collins says that women in politics are often judged for being middle-aged, instead of being acknowledged for all the experience they have. This is in comparison to many middle-aged men in politics, who are often seen as reaching the peak of their careers when they enter their 40s and 50s. Annette King has referred to former Prime Minister Helen Clark as a female politician who broke down barriers for women in politics, and how she experienced political criticism targeting her sexuality, physical appearance and her choice to not have children.

Representation of Women in Parliament

In 2011, National MP Maggie Barry became the first female National candidate for the North Shore, yet during this time she was told the North Shore “wasn’t ready for a woman”. The idea of enforcing a gender quota in Parliament has been voiced by some, but in 2015 former Prime Minister John Key rejected the idea stating that it would be a “token gesture” and would suggest that many women were only entering Parliament because they were female. But Key failed to address how can we encourage more women to enter the political sphere and take on leadership roles, when it is so heavily dominated by men.

Do women remain “a pretty little thing” in the political sphere?

In 2015, former rugby league coach Graham Lowe was asked whether Jacinda Ardern would make a good Prime Minister, to which Lowe responded by describing Ardern as a “pretty little thing”. Lowe went on to focus on Ardern’s appearance by commenting that “If she was [sic] Prime Minister at some stage, she’d look good”. The National Council of Women New Zealand Chief Executive Sue McCabe described Lowe’s comments as “dismissive and condescending”. By describing Ardern as “little” her abilities and political competence are reduced and the emphasis is placed on her inferiority as a woman, in a society that remains underpinned by a sexist culture. Lowe responded to the outrage which met his comments by claiming he was “trying to compliment her” as he “came from an era where calling someone pretty was one of the highest compliments”. However, Lowe’s response undermines the progress that has been made towards the equal treatment of women.

Are Female Politicians more than just “lipstick on a pig”?

Shortly after Ardern became the leader of the Labour Party earlier last year, former minority party leader Gareth Morgan, who founded the Opportunities Party, posted on Twitter that Ardern needed to prove that she was more than just “lipstick on a pig”. Morgan claimed that he was commenting on the rise of popular personalities in politics, which took away from the policies of different parties. However, Morgan’s comments reflect misogynist beliefs that remain in society, again focusing on the appearance of women rather than their capabilities.

Babies vs Female Politicians

Arden faced a wave of sexism in her first 24 hours as leader of the Labour Party, most overtly by being asked by Jesse Mulligan and Mark Richardson about whether or not she planned to have children. Mulligan framed his question by asking Arden whether she felt she had to make a decision between her political career and having children. However, there is a clear double standard as a recently appointed male leader would not be asked the same question. Richardson however claimed that New Zealand had a “right” to know if Ardern had plans to have children, and further stated that employers “need to know” the same of their employees. Richardson’s comments on the AM Show clearly show how entrenched sexism and misogynist beliefs are in society. We were distracted by the sexist idea that women’s primary role in society is to have children.

Ardern continued to face sexism leading up to last year’s election. Prior to one of the leaders’ debate, Mike Hosking asked Ardern what she would be wearing to the upcoming debate. Ardern responded by questioning Hosking whether he would be asking Bill English the same question. Ardern has commented that she has become used to experiencing sexism during her nine years in politics. Although Ardern remained strong and focused in the lead up to the 2017 election, she has been followed by constant criticism of her physical appearance and her role as a woman in society.

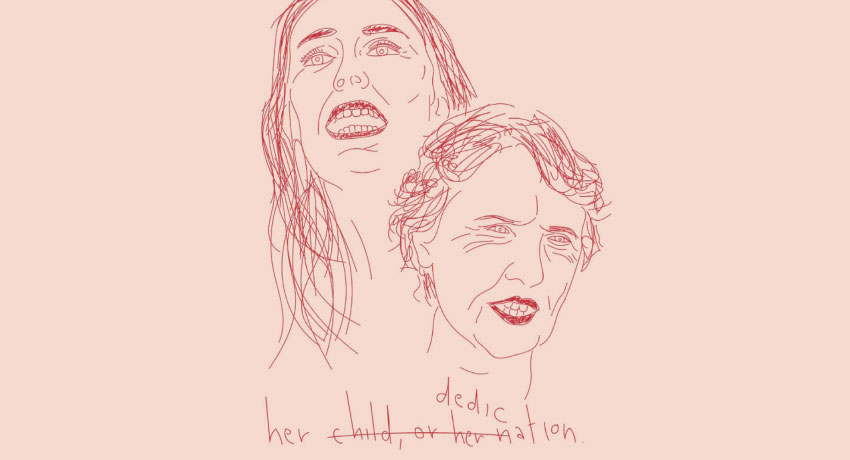

And as it turns out, the hypothetical of Jacinda’s family plans was not in fact hypothetical, as was revealed early this year with Jacinda’s revelation of her pregnancy. Predictably, there was a chorus of naysayers who took Jacinda to task. Among them was The Daily Mail’s Liz Jones (what else would one expect of that fine British institution?) who bemoaned that Jacinda’s pregnancy was tantamount to a “betrayal of voters”. The sexist assumption underpinning these complaints is that Jacinda, as a mother, faces the choice of depriving either her child, or the nation, of her dedication. Yet Jacinda and Gayford’s plan to have him raise her child demonstrates that sexist assumptions undermine what women can achieve, when society doesn’t hinder them.

Female politicians should be able to campaign without being questioned about their reproductive plans. There shouldn’t be an expectation that women cannot work and be mothers. Instead, the focus should be placed on their abilities and political achievements.