Music from the Memory

Portrait of diaspora students and their musical journey to Aotearoa New Zealand

In Memoriam: Rusiru Hettimullage

Rusiru was a Sri Lankan expat who taught and studied at the University of Auckland. He was a beloved English teacher and friend whose wisdom and warmth had left a lasting mark on his students and colleagues. He loved opera and classical compositions such as those of Beethoven, Chopin, Mozart and Tchaikovsky. He also covered Sinhalese folk songs. He was a true maestro of his craft, dedicating his life to learning and teaching even in his final days. His avuncular guidance had shaped the spirit of my writing and prose. He showed me the secret hymns of words that sing on paper. Though he is gone, his legacy lives on—in memory, in music, in us.

Iffah gripped the handle of her luggage as she looked down at the ground. Her purple hijab drapes like petals of orchids in bloom. She inspects the soles of her sneakers, the pair she scrubbed a few days ago, probing for a smidge of enduring dirt: the vestiges of her homeland. Some traces of soil, the imprints she made from her farewell footsteps. She looked again, now focusing on the carpeted floor. The legs of her fellow travellers were moving like stilts of bamboo, one step at a time. They were in a queue. The officers were thorough. She asked herself, could she pass the conscientious biosecurity?

Minutes ago, she alighted from the boarding bridge and gazed through a portalled opening to another world. In the line’s gradual march, her thoughts linger on the distant murmuring vibrations of alien but enchanting sounds emanating from the tomokanga (carved gateway): a birth canal, a transitional tunnel, a border’s edge of the past and a beginning’s promise to a future. Warbling songbirds, chirping cicadas, children’s laughter, the surging waves roar from the deep Pacific Ocean’s belly… they recede as she walks towards the sound rising to a crescendo… a melodious chant forthcoming, closer and closer to the entrance’s exit… then…

Stamp! Stamp! She was cleared of contaminants. “Off you go”, said the smiling guard. She went outside with her family. Her little brother yawns on their long flight from Kuala Lumpur. The winter’s thawing breeze pranced around the midnight still. Cold and shivering, her equatorially attuned body confronts the austral chill. At last, she left the Auckland Airport. The ethereal tones she heard were from the Karanga, a Māori welcoming call, the music that immigrants like Iffah hear first in Aotearoa.

In our casual introspection in the library one Friday afternoon, after class, Iffah and I embarked on an odyssey of our vibrant cultures and immigrant backgrounds. The past is the sound of music that beckons reminiscing. It quickens a memory as real and vivid as our navels’ crater—the invisible umbilical cord attached to our motherland’s whenua (placenta). How can we forget? What about the others? Can they hear the recollected pulse? Can they sense the nostalgia? What world of stories awaits us out there in the Auckland melting pot?

To examine our conjecture, we asked other diaspora students from the University of Auckland, and lo, confirmed what we had suspected.

Lester’s 7 Years by Lukas Graham

LESTER enumerates the musical artists that made him, and Daft Punk would be among the cream of the crop.

Lester’s SpotifyLester agreed to meet us in the Quad. He was armed with a Zima blue golf umbrella while the rainshower pitter-pattered from the canopy above. I skulked among the crowd, blending in, while observing a penguin wander from the nest a good distance away. He “waddles like a penguin”, so he said. But fascinated as we were to their natal philopatry, a penguin’s disposition to return to their place of birth, Lester was born and raised in Northland. At the turn of the millennium, his parents made the fateful decision to venture a life on New Zealand’s sunny shores, towards “better opportunities” for their children. Lester is currently finishing his BA in Psychology and Criminology at the University of Auckland but maintains an avid interest in the natural sciences.

On days like this, raindrops jolt a memory. Lester is on a manicured grass field, soaking wet. Water droplets dripped down his jaw. Lester studies his opponent, bearing a hockey stick, as he propels the ball away from their goal (striking circle). Their sticks were clashing, clapper noises heard. The sharp metal-like vibrations hurt his fingers, excruciating like needles in a pin cushion. Lester is disorientated. Water blocks his ear canal. And then, suddenly. Thud! A knock in the rib. He fell to the ground. Curling in agony. Piercing pain at the intercostal. His legs, chest and head were injured from hockey a few times before. Lester squinted at the ashen skies above. His head reels a steady ring, a tinnitus. He closed his eyes from the relentless barrage of rainwater. Dark. Drenched. Silent.

One song transports him back to that one summer’s high noon. Bright. Dry. Loud. He’s under the thatched roofs. Wooden pillars held the second floor of his whānau’s humble abode in the Guangxi countryside. It “gives me memories” he says, a tinge of nostalgia dredges his mind’s innermost core.

In Aotearoa, Lester’s dad would blast Mandarin and Cantonese tracks, through the stereo, on replay. Family picnics on the outskirts of Whangārei would be pelted by repetitive Maroon 5’s Payphone. “I actually despised the song because I heard it so much… I removed it from my playlist for, like, three years”, he said. That three-year interlude would reset Lester’s palate, making him re-appreciate Maroon 5’s Payphone years later.

We asked Lester what was the first song he fell in love with. Lester’s eyes glinted jauntily, his smile roseate, his supple, cherubic cheeks flushed—as if he was reminded of a puppy love. I could see it from across the room while taking mental pictures. This is a kidnapping, I told him half an hour ago. “We lured you to the Craccum office for ransom” unless you give our tongue-in-cheek due. He was shanghaied with us for two hours into a figmental voyage in time. Lester said his young love was EDM music, “Bone Dry by Tristam”, from his springtime, during an Eriksonian role-identity exploration. The music of his childhood.

Lester’s family enjoys a relatively placid lifestyle. They cherish the pianissimo, the restful, harmonious calm of life, which Lester has adopted in his formative years of musicophilia—from the ambient, lo-fi chill-hop lullabies played by YouTube streamers. This was his introvert phase’s leitmotif.

Lester’s foray into Daft Punk marks his coming of age, the expansionist era of his musical conquest. He started to get “comfortable talking to more people”. He got more “extroverted”. Chill vibes remain close to his heart. But when his EDM-verse was populated by Daft Punk, it was an aha moment towards newer frontiers. He listed his new favourites: Cardigans, Paramore, BENEE (from Auckland), Deftones, Porter Robinson, Sade and Sewerslvt. Lester also regrets missing out on the Coldplay concert last November. He had excursions into hip-hop culture and a fringe fascination with Eastern European musicology. It gives him a glimpse of how different songs mirror different cultures, he said.

Despite his diverse musical profile, Lester described his melodic appetite as 50-50, Kiwi and Chinese. He confessed, “It took some time to adjust [to] Chinese music”. He preserves his heritage with the music of his forebears, like a phantom limb outstretched to the past. He immerses in the doleful tenor of Jay Chou, the King of Mandopop. He poignantly said, “I’m gonna listen to them. I’m gonna make sure it retains the feeling”.

Iffah asked Lester how he felt as an Asian music lover boy sipping into the broth of the Western music sphere. He answered, “I think that’s perfectly normal. For some people they are obviously not like that; they’d like to stick to their culture. Since I was born here and I was raised here, in this environment, I think it is completely fine. I should know some of the cultures here, and I should also still retain my heritage and my ethnicity and where I’m from”. He added, “I’m Chinese… but I’m also Kiwi”. Lester’s personal identity melds both worlds in harmony.

Lately, he has listened to Chinese music less and less. He says, “Like 90% of my playlist is more European”. He is still fond of the old country sound, but he puckishly admitted that he “can’t really understand half the words they’re saying”. Lester’s Cantonese is “very shabby”. His Mandarin is no better. It was due to reduced exposure, a language attrition. He remembers his hometown; his whānau would only speak Cantonese. If you want to communicate, adapt: “do or die”.

For years, Lester hasn’t visited his parents’ place of origin. He visited Tianjin in 2016 but hasn’t returned since. He longed to be with his whānau from across the ocean, hoping for him and his parents to reconnect, learn more from his heritage, and “explore the country more”. Lester has a library of hobbies. He does online games in his spare time and endeavours in horticulture on the side. But history is on his shelf number one. A history buff. He said, “I like history because I like learning new events”, as he finds Chinese chronicles the most riveting.

Lester distinctly recalls a particular high noon with tendresse, back to the thatched roofs and the wooden pillars. He was sitting on an old Huanghuali chair: auburn and polished, a fad among the Ming aristocrats. He stares at a computer screen on the second floor. This was about a decade ago when the downstairs radio played a soulful Lukas Graham’s 7 Years in the background. It was the only English song that broke the string of “upbeat and positive” Chinese soundtracks.

Lester’s mind was in a bucolic agrarian land, a quaint and small village; he pictures it. The thoroughfares were lined with typical hovels and cottages, the roofs were browned with age, the walls were of rugged concrete, buffed earthenwares perched beside them. Some alleyways were unpaved. There was a pleasing but faint smell of burnt sandalwood from the neighbour’s window.

He would saunter in that one sleepy afternoon and witness the local shops open for a familiar pastime. Quick hands would shuffle around the blocky tiles that clink and clatter across the green square tables. Lester begged his relatives to train him, but he was deterred from the rules and strategy of mahjong. He watched the gameplay unfold behind their shoulders. The jade walls of face-down mahjong suits were like the rows of flowering rice in quadrangular paddies just beside the farming village. It was a plain and peaceful Chinese rural life near the Vietnamese border.

The chorus ends, “Once I was seven years old”, while the outhouse chickens were clucking to the tune. Lester impersonates the rowdy poultry, “bak-bak-ba-bak-bak”. He said the locals would enjoy those sinewy fowls for dinner.

He described his past to the melody of Feel It Still by Portugal. The Man, while his present, is a jazzy earworm of Smooth Operator by Sade. When I was about to ask our final questions, Lester looked at me with accusing eyes; they were like those of eagles. His fulgent grin expanded from ear to ear. The luster of Lester. Where are you going with this, Justin? Sade’s Smooth Operator reminds him of “good memories, close friends”. We ended the interview with Lester’s song of the moment, Daft Punk’s Digital Love.

Sam Zhou’s 螃蟹歌 (Crab Song)

Kunming City, China: 1,892 meters above sea level. A metropolis in its primal hustle and bustle, traffic horns blare in a cacophony of rush hour percussion. The sun has sunk in the Liujia District. Industrial smoke billows like a feeding spoon-worm. The Mingtong River spills, soil and swill, to the Caohai head of the Dianchi Lake. The Western Hills of Xi Shan all but witness the city’s dominating light across the waters. Through the passing dark, mitten crabs arise from their slumber and charge to their omnivorous forage along the lakefront. Seagulls were asleep on its pebbled banks. The residential towers soar through the skyline; some rooms are lit at random, like hives of unmoving fireflies. Somewhere in this urban jungle lived Sam Zhou.

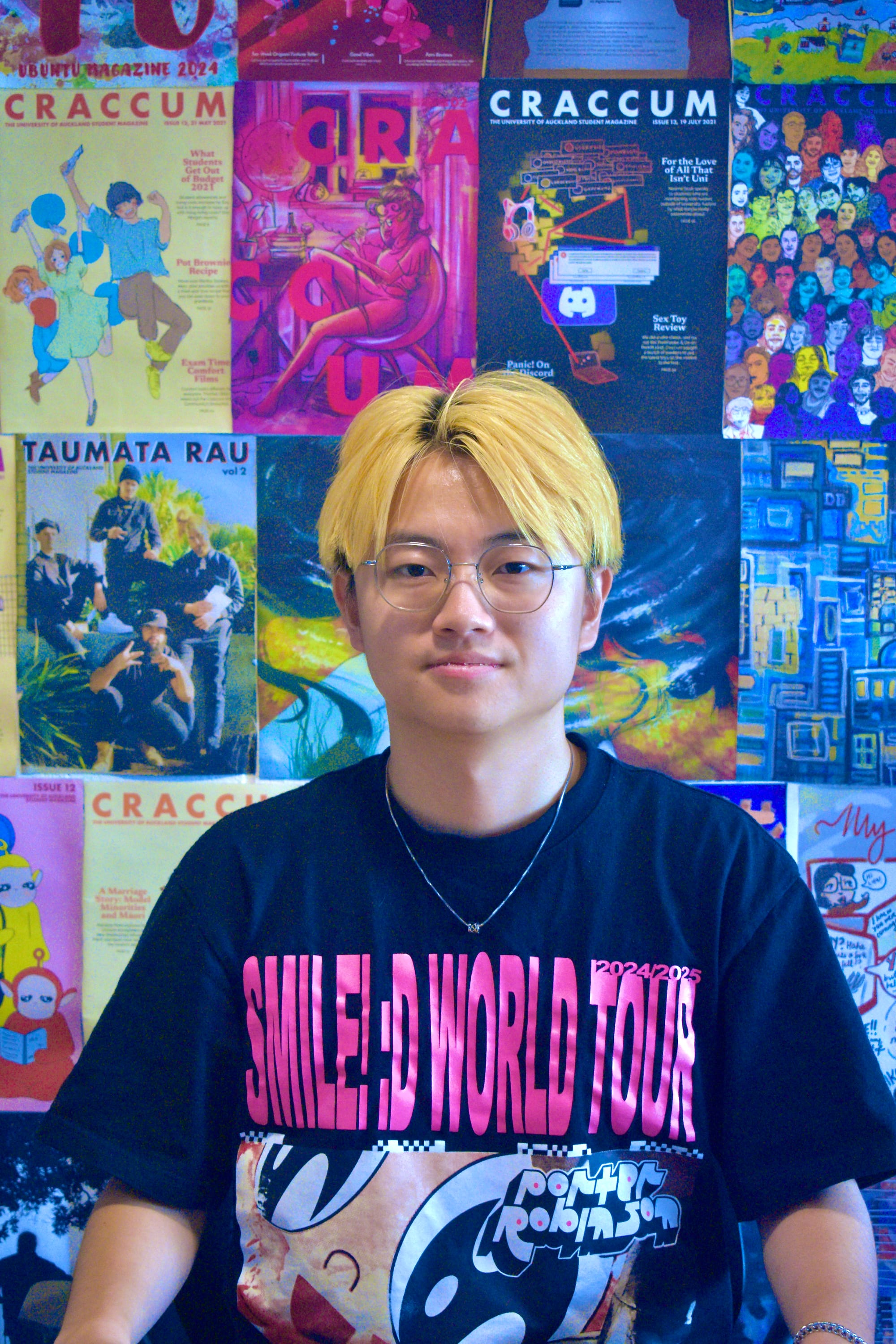

It was half past three on a clement afternoon, at the heart of the Quad, when I met a flaxen-haired Sam sporting Porter Robinson’s world tour tee. Sunny days remind him of Takapuna Beach and the long contemplative strolls by the seaside, to the salt-laden winds and the hypnotising waves lapping onto the land. “I really enjoy the sound of the ocean, when it’s quiet… that’s peaceful, and sometimes I reflect on stuff… just thinking when the sound of the ocean is in my ears… but I hate getting sand everywhere”, he said. Sam notices the rock crab burrows on the shoreline; the sea’s mesmeric noise has sieved a memory from the sand.

Upstairs, at the Craccum office, he drops his bag and fixes his wire-rimmed specs. He began to open up. “It’s actually pretty stressful when I grew up [in China] and a lot of pressure from school and stuff… I just decided not to remain there”, he glumly reveals. He perceived New Zealand as an “isolated little place” with the innocence of “untouched ground”—the virginal acreage of Tolkienian Valinor in the Years of the Trees. Sam moved to Aotearoa in 2018, leaving his family behind. “I was ready to gain a fresh chapter of my life because I was pretty fed up with my last one… I really like the more relaxed vibes here”, he said. He maintains regular contact with his family and friends.

Sam Zhou studies Linguistics and TESOL at the University of Auckland. “Growing up, I studied English at a pretty young age, and I found it pretty interesting… I just really, really love learning languages,” he shares. “I also look at a lot of movies, TV [shows], and a lot of music in English as well”, he said. Sam was reared to the Hollywood vernacular, mostly “relying on the subtitles at the time”. Sam is currently in the mood for the antihero archetypes like Matt Murdock in Daredevil, Walter White in Breaking Bad, Saul Goodman in Better Call Saul, and Dexter Morgan in Dexter—he maintains they’re crooked yet captivating. Sam was soused in the Anglosphere media early on; he assimilated in NZ like a duck to the waters.

We asked whether he felt a sense of longing for China. His porcelain face creased. His eyes sidled to a side. Sam ruminated intensely. When Sam finally answered, he said: “Yes and No… I’m very Chinese in terms of my ethnicity… I love the culture… the food. There [are] also people I care about that are still in China”. But he detests the pervasive “competing culture in schools, workplaces and stuff”. Sam objects to his former school’s draconian approach in teaching its students. The system was close to public shaming; Sam was never the complaisant Asian boy.

For Sam, music is “some sort of escapism… it’s something that everyone needs in their life”—a runway for a take-off to reverie and a flyby from living tribulations. “It’s also a way to connect to the artists who make the music. I get to feel what they are trying to write, what they experience, what they feel. And sometimes it’s just plain enjoyment, a way for me to connect with others that have similar tastes”, he said. Sam joined UoA BYO Music Club during his first year and currently serves as its Social Media Manager, promoting the club’s activities. “Everybody just goes into class [and] runs back home. You don’t get a chance to socialise, so I just joined the club… I’ve been in the club for a while, and I’m getting used to the other executives. I just felt like [it would be] natural if I volunteer to be a part of the management team”, he shares.

The first song he heard in New Zealand was a pop song, Sigrid’s Strangers, from a baking restaurant’s wall-mounted TV. It was an anthem with 115 beats per minute but with a sombre message of what reality has to offer. He profoundly connected with a song called Free by Broods, after settling on his Kiwi life all those years ago. “Broods is a New Zealand duo, and the song is talking about breaking free from something, which is the sort of what I’m feeling when I migrated here”, he noted.

But his immigrant life’s anthem is now what Chet Porter and San Holo have vocalised in their lugubrious but reassuring you’ve changed, i’ve changed. “I have changed a lot since coming here… but the ‘you’ve changed’ part symbolises China and my friends, my family. I don’t see them that often anymore. So, every time I go back, there’s always something different… I’m surprised by the changes every time”, he said.

Sam wanted to connect with the artists through their songs, like Jane Remover’s Search Party. “The song is about being overwhelmed by the idea of the future. You think about your future, and you sort of get anxious”, he said. Of late, his amour for the prevailing Chinese music had waned, “I think the sort of mainstream music gets very stale like every song sounds the same… it’s been that way for 30, 40 years or so. It’s kind of happening in English music as well, but not really as bad. But there’s still some underground music that I would listen [to] with my friends… I’ve come from listening to mainstream, popular songs to pretentious stuff. It’s like songs that are not as popular as mainstream stuff but are loved”, he said. In his very own société bohème, he and his musical comrades would dive into the free-spirited numbers of Chinese lyrical underbelly. “It’s a tiny subculture” with few listeners, he said.

“I also like concept albums that tell a story… good kid, m.A.A.d city by Kendrick Lamar… it’s about… [where] he grew up in, Compton, which is a chaotic place in terms of crimes. It’s talking about him being influenced by this violence… and that eventually resulted in one of his friends dying. So, he realised what’s happening, and he spiritually founded God, and he began a new life”. Sam relates to Kendrick Lamar’s narrative of renewal, which echoes his own rebirth, in a sense, from China to his relocation to the Land of the Long White Cloud, Aotearoa. Look at the Sky by Porter Robinson reminds him of his flight from Kunming to Auckland. He said, “The song talks about [a] fresh start and being hopeful about the next chapter”.

In spite of his ardour for his present Kiwi life, Sam still ideates his past with warmth and affection: the mellowed times when he didn’t have to worry about grades. Back in the Yunnan Plateau, in those high-rise residential buildings that towers over the Kunming skyline, a room was lit in effervescent glow, a faint gleam of honey amber on the corner lamplight, an upholstered armchair which sat a persona with a half-forgotten face. “I can kind of see her image, like a blur with a mouth that’s singing”, he recounts. It was a simulacrum of his grandmother chanting their dialect’s nursery rhyme, 螃蟹歌 (Crab Song).

Han Lee’s 아시나요 (Do You Know) by Jo Sung-mo

HAN LEE is an aspiring musician with dreams to connect the diaspora communities through the power of music.

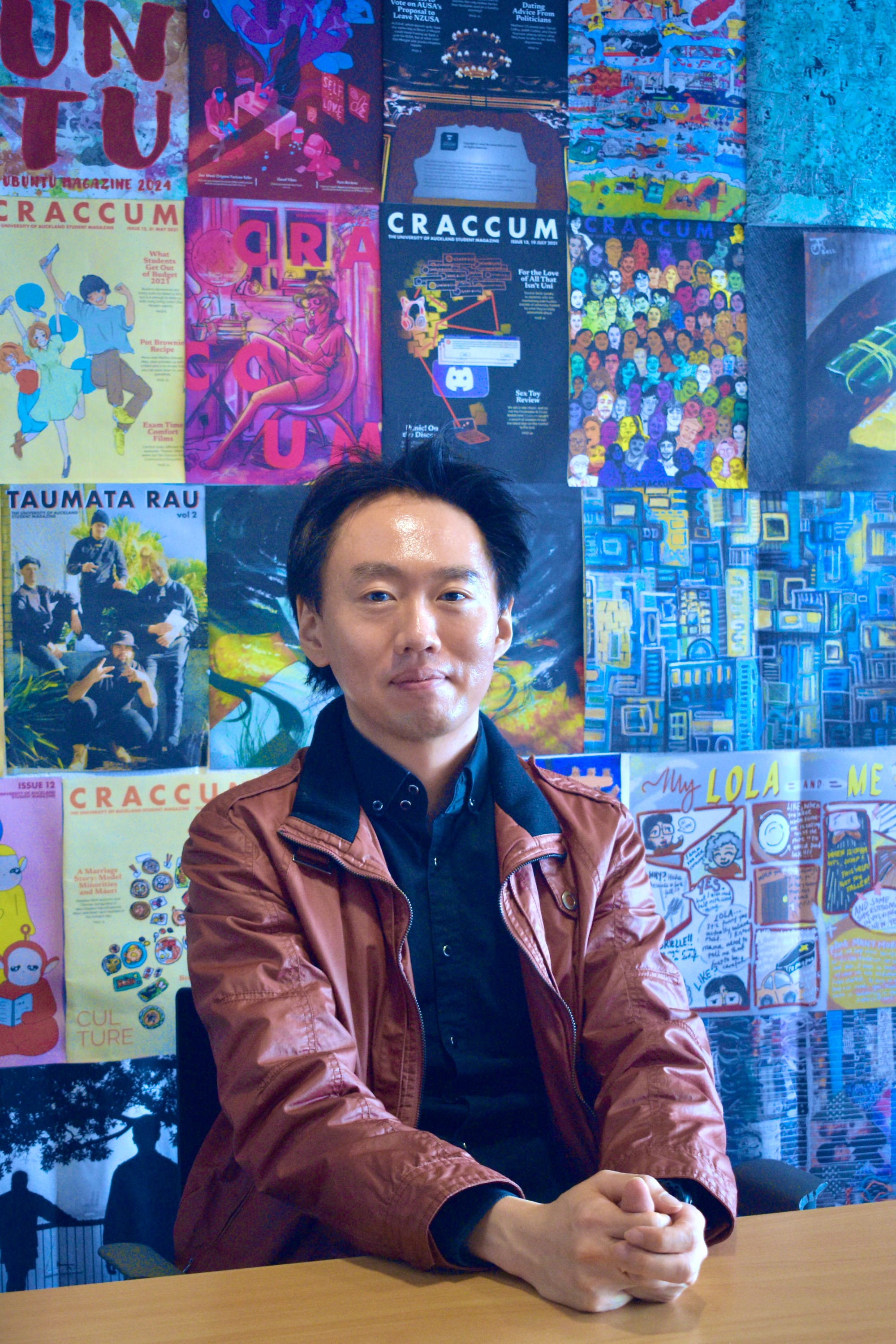

Han Lee’s SpotifyHan Lee is the urbane and self-effacing Korean-Kiwi musician who hails from South Island’s “Garden City” of Christchurch, playing the vocalist and impresario to an upcoming Pan-Asian Music Showcase Night on 28 June. His gracious Asian mien contrasts with his rockstar panache: suave tinted sunglasses, a sabled button-up shirt, a glossy chestnut jacket, and a smartwatch for quick voice memos wherever inspiration pops up. Han may eschew picante jjamppong (spicy seafood noodle soup), but his call to adventure is anything but avoidant.

Han Lee is a doctoral candidate at the University of Auckland, focusing on community psychology. He was born in the South Korean port city of Pohang, overlooking the East Sea (also called the Sea of Japan), but later moved to a small village in Gwangyang, where the touristic Jeju island looms on the horizon. In his teens, a visiting uncle convinced him to “travel to New Zealand” and “see if you like it”, he recounts. He moved to Christchurch, initially staying with his relatives while his parents remained in South Korea. Han lived in a homestay thereafter.

“I really like the ability to see wild animals”, he remarked. In fair-weathered Otago, he’s in awe to spot an albatross (tōroa), “the biggest bird in the world”, he says. A brisk walk on Dunedin’s coastline once revealed a colony of fin-footed pinnipeds. When he heard of trills and coos behind the charcoaled boulders lying by the shore, he stepped closer and discovered where the fur seals (kekeno) gather, sunbathing. One could easily mistake them for enchanting mermen, but he kept his distance, “it’s just dangerous” to touch them, he noted.

Though Han Lee completely embraced his Kiwi half, it wasn’t all sunshine and flippers adorbs. He shares, “As a young person, I did experience difficulty connecting with people from my own community, Korean people. Some Koreans are a bit different here. [Westernised Koreans] are different [from] Koreans from the mainland. They are more collective; here, they are very religious. I am not particularly Christian. I mean, I’m Catholic… a lot [of Kiwi-Koreans] are [Protestant] Christians. So I found it difficult to meet [like-minded] Korean people”. He also laments the small number of Korean enrollees in the Psychology department: “Many Korean people study Business or Medicine. My environment does not provide any opportunity for me to connect with Korean people… some Koreans are welcoming, but some are not… I think everyone is just unique”, he observed.

Han Lee is the quintessential man of the people. In South Korea, Han is the gregarious “oppa”, the revered cynosure of their campus democracy. “I actually said to people, don’t vote for me… and then they keep voting for me”, he said, beaming. Despite being introverted, he would lead the student body for about five years.

He harks back to his ancestral land. “I really like to connect with Korea, South Korea… North Korea also”, he says, with genial friends and family. “It’s my happy time when I was able to connect with so many friends… I was doing well, he said. He pines for its native cuisine as well: “Seafood is really popular in Korea. Oyster. Fish. Raw fish. I really love sashimi. I can’t have [enough of] it. I can have different shells, squid…” He also misses Korea’s jagged terrain. The native land’s memory refused to be forgotten as Han Lee imbibed the sound of music.

Han Lee often listens to music while travelling out of town or stationary at home. His auditory cells were attuned to the chordophone concertos of Antonio Vivaldi, Johann Sebastian Bach, and the virtuoso Niccolò Paganini of violinists’ lore. “I like orchestra… classical music”, he says. But his playlist also contains modern rock, pop and electronic genres. “At first, I have to listen to the melody, the sound, then I really pay attention to the lyrics”, he shares.

“Music is like my life. If I’m unable to do it, I feel I would be suffocating… It’s a way for me to overcome barriers. I’m very introverted. Sometimes I don’t want to do it… I feel embarrassed putting myself in public… but the thought that I can’t do music makes me feel I can’t live anymore”, he shares. Music alleviates his stress, mostly from the academic rigours.

Han Lee’s times in Christchurch and Dunedin were resuscitated at the sound of Fergie’s Big Girls Don’t Cry. He sheepishly admitted: “Sometimes I listen to really girly songs”, including the Norwegian pop duo M2M. We asked whether he still listens to Korean music. He says, “I haven’t really listened to K-pop a lot”, but his favourite K-pop band is GFRIEND and ITZY. The throwback music of Jo Sung-mo instantly teleports him through time and space back to the 90s Korean peninsula.

In 2000, Han Lee sat on a window seat on a Korean Air flight bound for Aotearoa, earphones plugged into a SaeHan MP3 player. For the whole lift, Jo Sung-mo’s sentimental ballad, 아시나요 (Do You Know), was kept on repeat against the mechanical droning noise of the jet engines. He described the music video as a soppy serenade of a diffident Korean loverboy to an elusive Vietnamese darling in the backdrop of war. “This kind of song reminds me of Korea because that’s the time that my life has been interrupted [by] my migration… When I feel excluded, loneliness, I have to listen to that. It reminded me of my happy, normal life without the effect of migration. It brings me strength that I feel I’m a normal person… I miss the time that I was completely happy, never experienced the challenges as a migrant”, he declared.

One day after migrating to Christchurch, Han Lee heard Breath by Breaking Benjamin from the shopping mall speakers. It was an “angry” song, Han Lee notes, but it was “cathartic”. Indeed, Han Lee became tethered to Linkin Park and My Chemical Romance in the first decade of the 2000s. They were the signature tunes of the dawning epoch of emo and punk rock. “More recently, I’m trying to listen to more K-pop because I do like some of the materials they have… I become softer”, he mentions. The tender-hearted Memory by IZ*ONE would verbalise his immigration life so far. “This song is about how this person [has] a dream, and they want to do it… sometimes it can be difficult, but… it’s a hope for the future”.

The riotous rock and pleasant pop songs were the fulcrum to Han Lee’s 2021 single White Noise where he urged his listeners to “connect the antenna”, a reference to the analogue televisions, for them to view the vast technicolour of racial diversity. Otherwise, they can only see a discordant static “white noise”. It was Han Lee’s artistic debut and diasporic billet-doux. At the heart of the immigrant plight is a molten core of intersecting struggles. Han, thus, combines these elements to compose his kick-off sonata.

Han’s musical contours started from a theme of victimhood, transitioning to that of victory. He’s currently producing newer jingles with Christmas vivace. He learned the piano, his main songwriting instrument, when he was in Korea. He plans to write a trilogy of conceptual albums. Han expresses, “My role is not about myself. I want to represent [the] Asian youth community… I have that responsibility to be able to represent them as [a] strong community”.

Han Lee devoted his adult life to migrants and refugees, particularly the youth of Burmese émigrés—officially consisting of 135 ethnic groups. “Refugee or Burmese communities are much better adapted… when we think about refugees… they’re traumatised in all of these things, but it’s not the case. They’re actually normal people. That’s what I noticed”, he said. Han shared the distressing hurdles that refugees undergo. “One key thing is separation from family… young people separated from their fathers went through trauma… the father [also] goes through traumatic experience”, he notes. The enforced separation tore families asunder, but they found hope for reunification in New Zealand. After the ordeal, they can heal and move on.

In his lone time, Han Lee adores the company of nature. One morning in Pohang, a young Han treks the adjacent Dongdae Mountains that gird the South Korean east coast from Ulsan. The sky is overcast; the fog barely lifted, a hint of coming winter in the wind. There were mottled, yellowish, Ginkgo leaves and flecks of umber pine cones underfoot. He inhales the dewy autumn air, cosying up in his parka. Han followed a beaten path he learned by rote, but midway, he hazards the road less taken.

Laboured breaths. Precarious trail. Halfway, he nearly stumbled—flat to the bitter earth. But Han Lee is undaunted in the face of adversity. The view from Dongdae’s mountainous brow was a sight to behold. He looked to the east, a cerulean maritime grassland and scattered islands afar. He looked back to the forest below, an evergreen arboreal sea where Pohang City is at its cradle. Han Lee, still awestruck, sounded his barbaric yawp against the roof of the world: a triumphal roaring forte. He reclines in exhaustion, a flake of snow lands on his forehead. The journey to the summit is as rewarding as the destination. He was a kid then. But for Han Lee, the odyssey has barely begun.

Han Lee's White Noise on Spotify

During the interview, I was flanked by Iffah donning her lavender veil. We confide in sotto voce to punctuate the silent ponderings of our interviewees. Outside, on our way to Waitematā, she told me about her personal transformation from a “dorky” Malaysian girl to a headstrong free-thinker, coming to Aotearoa. Her musical taste would range from Sungai Lui by the Malaysian artist Aizat Amdan, whilst finding herself “Kiwified” to the gossamer alt-rock of Blue Light by Mazzy Star.

On my first day in Aotearoa, I overheard my Indian neighbour’s loudspeaker playing Bollywood Indi-pop. I looked at my phone and clicked on Spotify. My last played song is the one on repeat since I left the Philippines, Lola Amour’s Raining in Manila. I pressed shuffle and, as if by serendipity, the ensuing song was Poi E by Patea Māori Club, a fitting theme song after the crossfade. I maintained playlists like journals throughout the years. I came from the 70s rock legends and found myself engrossed in Tokyo City Pop and Jazz Fusion later. Still, Raining in Manila are memories of red gumamela, verdant fields of palay grain, a monsoon's downpour, smell of petrichor and sampaguita... Writing this piece was an experience, a journey to cerebrate my own immigration.

I closed the Word document, giddy and euphoric. I stepped outside for a walk, rubbernecking at the colossal super-organism of the musical hive mind. The very memory of the human race is the music that surrounds us. Aotearoa is in metamorphosis, blending a medley of peoples and cultures together. Emerging from the chrysalis, whole and transformed. We are the composers of our evolution, a symphony in the works, a humbling ensemble of unified and interwoven heritage, rich and mellifluous as a psalm, grand as the motions of galaxies: like Tolkien’s Ainulindalë—a world sung into being. Music and culture were not etched on a marble arch that waits in changeless monotony, but an ongoing chord progression whose staves are drawn and redrawn on the homeland of our choosing.

I would like to extend my sincere thanks to my friend, Iffah Mohamad, whose personal story is featured in this piece. While I was primarily responsible for the writing, her vital role in the interview process, as well as her thoughtful feedback during the revision stages, greatly enriched the narrative and overall quality of this work.

Iffah and I were both former students of the late Rusiru Hettimullage. He tragically passed away on 29 March 2025 at the age of 36, while currently in a teaching position at the University of Waikato College and pursuing a PhD at the University of Auckland. His remains were repatriated on 7 April and interred on 11 April in Sri Lanka, south of Colombo, his homeland. Rusiru is survived by his loving parents. He is their only child.

O Captain! My Captain! Our fearful trip is done.

Rest easy, Maestro, in Peace, in Nirvana, to the awakened sun.

Thank you for reading.

If you have any questions, comments, or would like to get in touch, please feel free to contact me:

📧 Email: justinagluba@hotmail.com

📸 Instagram: justin_agluba