Craccum Throwback | ICEHOUSE's Iva Davies Interview

An interview with Aussie synth-pop legend Iva Davies on legacy, memories of collbaorations and a forgotten 80s supergroup based in Japan. [Craccum #20, 2024]

Originally Published 24th September 2024 in Craccum #20, 2024.

ICEHOUSE’s hits are essential to the 80s songbook of Australia, New Zealand (and the rest of the world). If the band’s name doesn’t ring a bell, perhaps their earworms do: Great Southern Land, Hey, Little Girl, Crazy, No promises, Street Cafe, We Can Get Together etc. I enjoyed talking with the mastermind behind the band, Iva Davies (songwriter, vocalist and guitarist), on ICEHOUSE’s legacy and some of his memories from their rise to fame. Iva Davies He also opened up about his experiences during the little-known collaborations with fellow synth-pop legend, Yukihiro Takahashi, in Japan during the mid-1980s. I and Craccum would like to thank Iva for generously giving his time. And if you’re a fan of the ICEHOUSE sound, they’re performing in NZ next January.

What colour are you feeling today? Surely Electric Blue?

Ah, well it's a fairly grey day here in Sydney. I don’t react well to persistent rainy weather, it's only gotten worse as I’ve got older, so I’d say grey.

What was the last album you listened to?

A classical piece called Pictures at an Exhibition by Modest Mussorgsky, orchestrated by Maurice Ravel. I rarely listen to popular music, it just reminds me of work.

Favourite place in Aotearoa New Zealand?

I’d say Queenstown. We’re touring there next year and they have this fantastic Japanese restaurant there. To be honest my partner is coming over with me just for the food there.

Now, for a tricky one, what do you think makes or breaks a hit synth-pop song?

That's an interesting question, I would say most of what I did was dictated by the technology itself. For example, I have a piece sitting in front of me right now: a Sequential Prophet 5 Rev3, a revolutionary machine. I’ve used it throughout my whole career from the late 70s, right through to the last time I recorded in the 2000s, which is an incredibly long time to use just one instrument. The quality of the song comes from the sound of the instrument, such as that single note at the start of Great Southern Land.

Speaking of ‘Great Southern Land’, to me it is a bit like ‘Born in the U.S.A.’Speaking of ‘Great Southern Land’, to me, it is a bit like ‘Born in the U.S.A.’, where your lyrics present a critical view of the country in the title, but the song also has a patriotic anthem-like quality. What are your thoughts on the legacy of songs like yours from that era with a political edge in Australia today?

I always took a position of not wanting to give people the answers, or push a particular point of view. On the other side of the coin, you have bands like Midnight Oil who had an incredibly forthright message in their lyrics which they wear on their sleeves. I wanted to pose questions and let people think about them. I remember going to a great deal of trouble to weigh the scales when writing the lyrics of Great Southern Land. For example, I chose to use two verses, instead of the standard three. The first presents a kind of black/white view and the second a more ancient/modern view to balance the discussion. I’m kinda proud at 25 that my thinking was that peculiarly mature.

Great Southern Land by ICEHOUSE. Written by Iva Davies.

Standing at the limit of an endless ocean

Stranded like a runaway lost at sea

City on a rainy day down in the harbour

Watching as the grey clouds shadow the bay

Looking everywhere 'cause I had to find you

This is not the way that I remember it here

Anyone will tell you it's a prisoner island

Hidden in the summer for a million years

So you look into the land, it will tell you a story

Story about a journey ended long ago

Listen to the motion of the wind in the mountains

Maybe you can hear them talking like I do

They're gonna betray you, they're gonna forget you

Are you gonna let them take you over that way?

In 2024, ICEHOUSE is celebrating the 40th anniversary of their third album, Sidewalk. Where do you feel that album sits within the larger discography of the band?

We had ups and downs like most acts, and in comparison to the albums surrounding it, Sidewalk was considered a commercial failure at the time. It was a strange period. I decided to produce it myself, which was probably a mistake in hindsight, but it was just something I had to do to get it out of my system. Most of it was recorded in Sydney, but only half the tracks had lyrics, which was tricky to get around. So, I booked another studio in L.A. in 3 weeks time, then sat on a Hawaiian island with that deadline hanging over me to come up with the lyrics. When I got to L.A. I just sang the vocals in one take to get it over with.

Following up on that, what can you tell us about your latest release 1984 Live Desk Tapes?

That was a complete accident! Andy Hilton was our front of house man for our Sidewalk tour, he also engineered the album. He moved to the US decades ago, and we’ve been in intermittent contact since, sending an email around birthdays and such. Not that long ago, during idle discussion, he mentioned he had these tapes recording the Sidewalk tour from his mixing desk. And I said, “You what?!!” It was a real treasure trove.

[Arts editor's note: it’s a great live album btwSpeaking of ‘Great Southern Land’, to me, it is a bit like ‘Born in the U.S.A.’, where your lyrics present a critical view of the country in the title, but the song also has a patriotic anthem-like quality. give it a listen]

When you were 21, you took the leap from being a classically trained oboist to a rock star pursuing popular music. Do you have any advice for young people who might be facing a similar career crossroads?

The main piece of advice which I have been giving young people over the years I feel is redundant now. There is no doubt in my mind that being highly trained in music theory was an incredible advantage when constructing pieces of music. But it is really less applicable these days because people don’t make music conventionally so much, you can be successful with just a laptop.

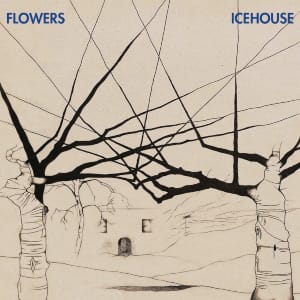

Also, what was it like being forced to change your band name for legal reasons?

It was a bit of a wrench really. We were about to release our debut album ICEHOUSE on our international label, after it was already a big success in Australia and NZ. But the company said we couldn’t use our band name, Flowers, because it was already taken by some other band. So they had this competition out of their London and L.A. offices to rename us, and they settled on ‘Industrial Chili’ [Laughs]. It was pretty horrifying. So, we used simple logic and realised we have two names associated with us, Flowers, and ICEHOUSE. So we chose ICEHOUSE and we did a short local tour to announce the name change before taking off to pursue international fame. Band names are incredibly important, you cannot imagine! That is what you are going to be associated with forever!

You’ve performed and collaborated with many musicians over the years, including some you covered in your early days, like David Bowie and Brian Eno. What’s it like not just meeting but working with your Heroes?

The Bowie one was amazing, opening for his 1983 Serious Moonlight tour by far the largest thing we’d ever done, but because of that I didn't get to spend real time with him. I mean he was absolutely swamped and suffering from ridiculous success, playing to 50, 60, 70 thousand people every show. We had a few conversations but didn’t hang out. He couldn’t go anywhere either as he needed a bodyguard with him, and he nearly got killed at a nightclub one time. A number of years later I got the chance to spend some real time with him but that’s another story. Funnily enough, we were actually given an offer to tour supporting Peter Gabriel at the same time too, but I’m glad we picked to go with Bowie.

Eno was remarkable, and I was a big fan of his early solo albums. The producer I chose to work with on our 4th album Measure for Measure (1986), Rhett Davies, was the producer of Roxy Music, and of course knew him quite well. I was in this tiny London studio recording the backing vocals for ‘Cross the Border’, when I mentioned to Rhett I was aiming for a Brian Eno style and he discovered I was a fan. So he nonchalantly said, “he’s living in a basement over there, I’ll let him know.” And I was freaking out. So the next thing I know, Brian Eno walks in unannounced about 30 minutes later, and starts singing the back-up vocals I’d written to be in the Brian Eno style!

'Crossing the Border' official music video, featuring Brian Eno's backing vocals.

The thing is we did a lot of covers in our early days as Flowers, mostly T. Rex and early Bowie, and Eno. But never did we once cover Roxy Music, even though it’s somehow out there that they were this big inspiration for us.

[Arts editor's note: Sure enough, Wikipedia claims they did covers of Roxy Music. Don’t trust everything you read online, kids. Trust Craccum instead.]

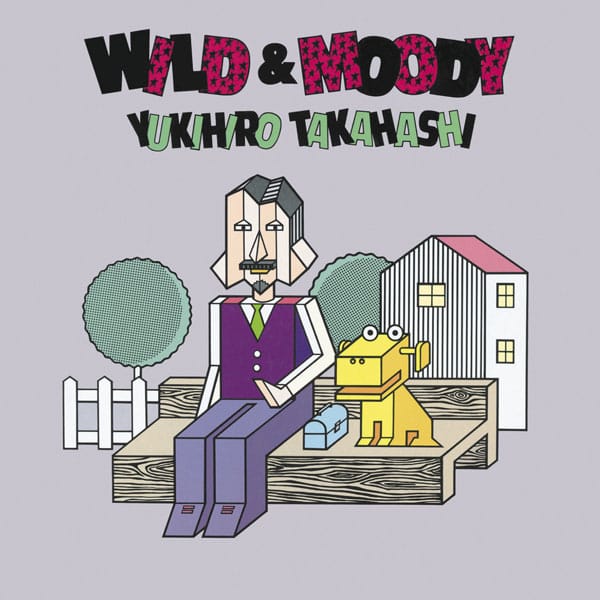

One of your lesser-known collaborations was with Yukihiro Takahashi, the drummer/vocalist of the Japanese electronic band Yellow Magic Orchestra. How did that collaboration come about?

At the time, Yukihiro Takahashi had made a habit of trawling the charts looking for songs he liked and would recruit the artists to write English lyrics for music because he was uncomfortable with his English skills and was looking to find success outside of Japan.

'Hey Little Girl' official music video.

So when we had this big hit off our second LP (Primitive Man, 1982) called ‘Hey, Little Girl’, I appeared on his radar and received an invitation to come to Japan in 1983. I wasn’t the first English-speaking lyricist he’d worked with in this way, before me it was Bill Nelson (of Be-Bop Deluxe), and before him it was Robert Fripp (of King Crimson).

Did you experience any ‘culture shock’ when working in a Japanese recording studio, compared to an Australian or western one?

Definitely! [laughs] I wouldn’t consider myself to be a good collaborator in general, but I’ll never forget that experience recording with Yuki, it was fairly daunting to me.

I arrived in Tokyo and was driven from the airport in air-conditioned comfort and spent about an hour at the hotel before I was expected at the studio. I remember looking out my window at this Shinto temple 100 metres down the road and thinking I’d walk to it while I waited. I was wearing light clothing and shorts, but the second I stepped out the door into the Tokyo summer I was drenched in sweat! [laughs]

Anyway, when I got to the studio later that day there were more people than I’d ever seen in a control room before. They had the musicians, interpreters, managers, tons of engineers and assistant engineers wearing these white gloves. Then they played me this instrumental track, which was for the song ‘Walking To The Beat’, and straight away afterwards the interpreter goes: “Yuki thinks you should try to write some lyrics”.

'Walking to the Beat' music video, featuring lyrics by Iva Davies.

I said, “Yea sure”, but you see I was expecting to go back to the hotel with my Walkman at least overnight to figure out the lyrics. But they keep looking at me. And I was like “Wait, you want me to write them now?”. They all nodded yes. And being put on the spot I freaked out completely inside.

So I sat on the studio floor for about half-an-hour listening to this music and writing some lyrics. And when I said I had finished, the interpreter came over the intercom saying “Yuki would like you to sing them now”!

So I stood at the microphone and sang them off the page as I heard them in my head, and of course I made a few uncomfortable mistakes. So I asked if they would mind if I could have a second go as I had a sneaking suspicion that my rough vocal guide would end up on the final cut.

From there, Yuki kind of parroted over those vocals usually. I’m pretty sure on the final mix at least 40% of my voice mixed in with his. He was quite heavily dependent on collaborators for English vocals.

They’re far less casual in the studio, you’re here for a job and we don’t muck around. That work ethic is part of their culture. It was so intimidating with everyone waiting for you and staring at you. No one left the room the whole time.

In your second studio album collaboration with EGO (1988), you actually sang on one of the tracks, ‘Dance of Life.’ What do you remember about the creation of that track?

My second experience was quite different. This time there wasn’t a pre-recorded instrumental and they had my main workstation in the studio, the Fairlight CMI. So I was able to write ‘Dance of Life’ from the bottom up.

Dance of Life (1988). Written by Iva Davies and Bob Kretschmer for Yukihiro Takahashi.

We were on the 17th floor of the EMI building in Tokyo and at a certain point the building started swaying from an earthquake. None of the Japanese missed a beat, but I completely freaked out and had to get Bob Kretschmer (of ICEHOUSE), who was working on the track with me, to kinda hold my hand though that! [Laughs]

One footnote is that at a certain point this Japanese man walked into the studio with a long black overcoat and Yuki suddenly got very excited and animated. That man was Ryuichi Sakamoto (of Yellow Magic Orchestra). He’d just invested in a DAT portable recorder and had been wandering through Tokyo that morning recording crowd noises. Yuki was so taken by it that those recordings ended up getting thrown into the front of ‘Dance of Life’, which you can hear if you listen to it.

[Arts editor’s note: Fun fact; Bob Kretschmer would later go on to become a big Hollywood wigmaker; an example of his work is Captain Jack Sparrow’s dreadlocks]

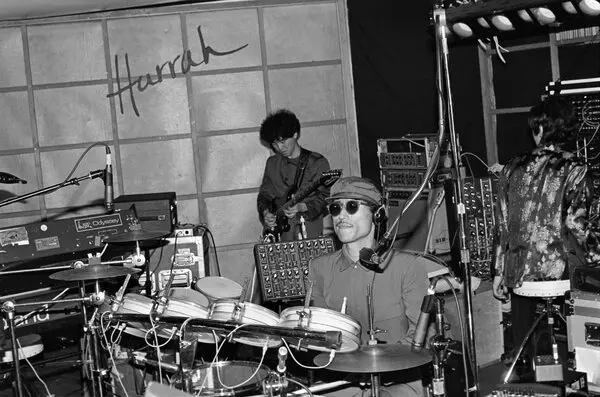

You were also part of Takahashi’s touring band in the mid-80s for a while, which was kind of a low-key international supergroup. Do you have any stand-out memories about that tour and the band?

In 1984, I was also given an invitation to be part of the touring band as lead guitarist and a vocalist as a replacement for Bill Nelson, and I sang one song at the shows: ‘Helpless’, which was a Neil Young cover.

When I was in Yuki’s band there were some local Japanese stars and this bass player ironically called Rodney Drummer. Yuki didn’t play drums at all as he wanted to be at the front, so instead he had this amazing drummer Steve Jansen (of Japan [the band, not the country]). Steve collaborated more extensively than I did with Yuki. Steve’s a lovely guy. We became great mates over that tour, hitting the clubs together, chatting till sun came up and playing cards. He was the first drummer I’d met who could play to a click track, which I didn’t even know was possible, and it suited me down to the ground. So I invited him to play on the 4th ICEHOUSE album, Measure for Measure, but I was sad we never got to tour that music together. We were all so busy in the 80s and quickly moved onto the next project.

The concert tour we did was also extraordinary and nothing like I’ve ever seen. We played very early in the evening at 6 pm to these massive theatres. The whole audience was seated, incredibly attentive and quiet, but would suddenly erupt into applause in between songs, like crowds did for The Beatles. It was like Beatle-mania really. When we left the venue they had to send decoy cars going in the opposite direction as Yuki would be followed by hordes of young female fans. The entire culture around musicians in Japan was so extraordinarily different too. At that time Yuki had his own TV show and a string of clothing boutiques. They really became an all round media phenomenon. Japan was well into the kind of sponsorship deals you see today a decade before anywhere else.

Overall, what did you make of Takahashi? Was there anything you felt you learnt or took away from collaborating with him?

Our personal interactions were very limited by the language barrier. But the first day I was in Tokyo, when I arrived at the studio, the main engineer was in the recording room fine tuning Yuki’s drum set. He’d been up all night getting them just right. Yuki was a tiny guy, even shorter than me, and skinny as a rake. When Yuki arrived, he went up to the kit and tested it out. I don’t believe I’ve ever heard a louder drummer, he was an absolute powerhouse. Although I never actually heard him play again, I could tell he was a legendary drummer. He passed away a few years ago and it was a great loss because he was a brilliant musician.

In the Yukihiro Takahashi band, my head exploded. It was a truly extraordinary experience using a click track to play live. Yuki was well ahead of his time by having his whole touring band play with these headphones on listening to a synchronised click track. We even had our own little mixing consoles! Ever since, and to this day, I always use a click track with my live band. In 1985 when ICEHOUSE needed a new drummer, I auditioned this 17 year old young man with a Walkman and with a click track playing. And he’s still our drummer!

Lastly, is there anything you want to plug or shout out to our readers? How can we support your music?

ICEHOUSE will return to NZ next January to support the Summer Concert Tour 2025. They will be supporting fellow Aussie rock legends Cold Chisel for their 50th anniversary tour alongside Everclear, and our very own Bic Runga. They will be performing three out-of-Auckland shows in Queenstown (January 18th), Taupō (January 25th) and Whitianga (January 26th). Tickets are on sale now! Also, follow them on Insta @icehouseband.

Here’s what Iva had to say about ICEHOUSE and Cold Chisel:

We go way back. Cold Chisel was actually part of a revolution in the Australian music industry. Back in the day, this company called Premier Artists had a monopoly stranglehold on Australian music with over 200+ bands signed. If you wanted to play live you had to go through them. There were these two managers who realised the two bands they were managing generated half the revenue for Premier Artists and they weren’t getting a fair cut. The bands were The Angels and Cold Chisel. So they broke away, and took on a third band as a kind of apprentice to open for Cold Chisel, and that was us when we were Flowers. And we’re still opening for them to this day, so we haven’t graduated from our apprenticeship yet! [laughs]