“Down the rabbit hole.”

That was my first impression of the contemporary art exhibition, happiness is only real when shared at Gus Fisher Gallery. Upon entry, the kaleidoscopic dreamscape of neo-deco colours kindly sweeps you away from Auckland CBD’s concrete greys. One minute I was hurrying past lawyers and bankers on Shortland street with medium-sized Atomic coffee cups, and the next I was Alice at the Mad Hatter’s tea party. However, instead of a banquet, I was a guest to Mark Schroder and his Bureau of Happiness.

happiness is only real when shared is a three-artist exhibition, hosting works by Wong Ping from Hong Kong, Mark Schroder from Aotearoa, and Pinar Yoldas from Turkey and the USA.

“I decided we would limit the number of artists to three, but these three artists are the least minimal artists I can find,” said Lisa Beauchamp, curator of the exhibition. “A key idea was to jolt us into an alternative world, away from the throws of daily life and the fears and isolations of COVID-19. Yet it is also an examination of the post-2020 consumerist mindset and corporate landscape.”

As an objective fact, the works are colorful. It’s playful, it’s engaging, catches the eye, demands attention, and can almost pass off as cheerful, at first glance.

As an objective fact, the works are colorful. It’s playful, it’s engaging, catches the eye, demands attention, and can almost pass off as cheerful, at first glance.

According to Lisa, the exhibition is a response to the gallery’s 2019 exhibition We’re Not Too Big To Care, which featured a diverse range of 16 international and domestic artists from Aotearoa, Australia, China, Canada, the UK, and the US. The current exhibition continues the examination of modern capitalism through the lens of consumerism, mass production, and corporate hierarchy from a wide variety of cultural contexts.

The series also references the historical significance of the gallery’s location on Shortland Street, as the first commercial street in Auckland before Queen Street.

“Purposefully cliché,” and that is the point.

“The exhibition begins with Wong Ping; you are learning about these fables and alternative views of society’s morals. You then encounter Mark’s installation and this familiarity of how these powers are interacting with us in a workplace. Finally, it finishes with Pinar’s work of looking into the future with AI and this outer layer of control,” said Lisa.

Wong Ping: Fables (2018-19)

Wong Ping is a Hong Kong artist whose animated series, Fables, is featured within the first gallery space. The exhibition is titled after one of his animations “happiness is only real when shared.”

“Before doing Fables, I did a lot of research and read many big-name fairy tales, and I found they weren’t really practical for today’s society. For instance, I know I have to be good to my parents, but it’s hard to do that when I’m away a lot and I can’t spend more time with them,” said Wong in an interview with Ocula Magazine. “I wanted to write something that’s very honest, that tells kids that they don’t have all the time in the world to be with their parents, friends, or lovers—that’s just a fact.”

His five fables include satirical, absurd tales of animal protagonists’ journey through the media-saturated, capitalistic modern-day Hong Kong. His animations have a nostalgic quality that nods to the era of neon-colored cartoon characters and beeping arcade games. They capture the essence of a turbulent Hong Kong under various layers of power, tension, and control.

“It’s not a straightforward critique to modern consumerism. Because Wong Ping is based in Hong Kong, if you want to have political content in your work it has to be very hidden,” said Lisa. “With Wong Ping, there is always a twist, and it’s this twist that makes you stop and think.”

The fables are often highly complex and multi-layered tales of self-made “heroes” caught in a web of love, suppressed sexuality, narcissism, and self-acclaimed righteousness. The fables feature ludicrous yet jarringly relatable characters such as an insect-phobic tree, a social media obsessed chicken, and a self-made billionaire cow. In the end, the viewers are left with the bittersweet tagline that almost commands to be read, repeated, and memorised ––– “happiness is only real when shared.”

Mark Schroder: Fortune Teller (2021)

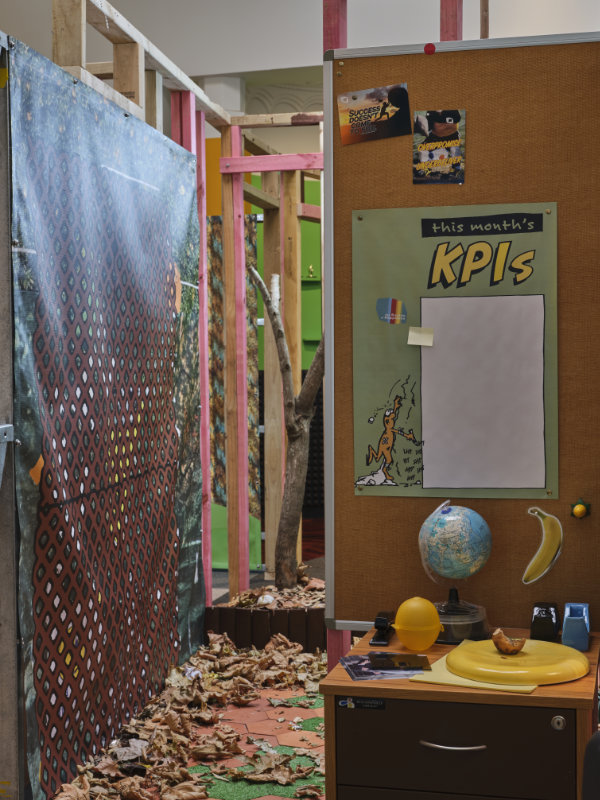

The main booth of the gallery is occupied by the Aotearoa artist Mark Schroder’s maze-like installation Fortune Teller. Mark is an artist as well as a financial lawyer –– a dual identity that gives him a unique insider-outsider look into Auckland’s corporate culture.

“During another exhibition I did, my lawyer world and my art world collided and some of my art friends thought my law friends – all these people in suits and ties – are part of the installation,” Schroder told RNZ in an interview.

The installation is home to The Bureau of Happiness that specialises in the well-being of employees. The overly cheerful and cliché motivational posters, cheese blocks, plastic bananas, toylike ceramic objects, yoga balls, and sneaky notes omnipresent in these old-styled office spaces are juxtaposed alongside dried leaves, dead tree branches, and bare wooden structures. The post-apocalyptic office space feels incredibly lonely.

Lisa disclosed to me that once a cleaning staff at the gallery actually started to clean up the dried leaves and branches of the installation. “Maybe they thought it was an actual office space,” Lisa laughed. “I was like ‘God, don’t touch the leaves. It’s an artwork!’”

While the installation is seemingly absurd and surreal, there is also a cynical undertone that questions the sincerity of these mottos and corporate slogans – do institutions really care?

“Being a lawyer on Shortland street, you catch glimpses of different corporate values and mottos and they all start to blend into one. Why do you need to say ‘respect, honesty, and integrity,” because shouldn’t that be inherent to what you do without having to say it as a promotional line?” asked Schroder in the interview.

Continuing Wong Ping’s search for happiness amongst a concrete jungle, the question of “real happiness” is again reiterated by a motivational poster from The Bureau of Happiness: “What use is success if it can’t be shared? What happiness does that bring?”

Pinar Yoldas: Kitty AI (2016)

The exhibition finishes in the third and last booth hosting Pinar Yoldas’s animated video The Kitty AI. It is a speculative fiction that explores the possibility of a world run by an AI that has taken the form of a cat to increase its likability.

“I was exploring an alternative to current day politics, specifically a democracy that integrates A.I.” Yoldas said in an interview with UCLA. “My practice explores art in the Anthropocene in order to engineer effect and critical thinking in the viewer. I design multimodal experiences in an attempt to create intellectual, discursive disruptions and provoke long-lasting activism.”

Yoldas’ work ends the exhibition on a futuristic note that takes the conversation on control from the micro-levels of individual characters and spaces to the macro social-political makeup. The kitty AI with the robotic baby voice is eerie yet almost strangely likable.

“With the Kitty AI, it’s incredibly surreal but it’s incredibly real at the same time,” said Lisa. “It’s happening all around us: everyone can be tracked, everyone can be found. With COVID, we are checking-in everywhere. All these other layers of control around us may be invisible but they are absolutely there.”

“Acutely self-aware.”

The satire and subtleness of the artworks are what makes the exhibition powerful ––– that we as viewers need to find our way through the maze of candy wraps and clichés.

“It goes around in a circle: the surrealism almostmakes us more self-aware. It’s that satire and cynicism that masks the serious undertones, but they are absolutely there and, intentionally, they do come through,” said Lisa.

In a way, we are inadvertently spoiled by easy answers and solutions in the modern media world –– “just google it,” they say.

As a result, we almost normalise our daily doses of “tragedies” – breaking news, death, atrocities reduced to a single app notification. By not choosing a gloomy and serious tone for the exhibition, happiness is only real when shared forces us to investigate the authenticity of its own happiness. The works’ denial of a single solution to the tension between the search for happiness and consumerism stimulates discourse and contemplation from the viewer.

Unable to resist, I asked Lisa for an easy way out.

“Do you think the exhibition offers an answer as to whether social justice and capitalism are compatible?”

But I think she suspected my motives.

“We are putting out these commentaries from the three artists and leaving it open,” she said. “I always resist the desire to try and find a resolved answer because I don’t think that is possible, and I don’t think that it is the purpose of exhibitions.”

The exhibition happiness is only real when shared will show at the Gus Fisher Gallery with free entry until the 8th of May.