Craccum Throwback | A cartography on filmmaking, criticism, and nostalgia

A constellatory reflection across multiple conversations with friends on the ethics of making, spectating, and remembering cinema.

*For a multitude of reasons irrelevant to the scope of this piece, this never saw the light of day on the print issues of Craccum of last year (granted, the piece was originally 7,300 words long), was never promoted on any social media, was never uploaded on the official website, and remained buried underneath the multitude of film lists and reviews of Craccum's Letterboxd account. There will undoubtedly be many more articles that will further bury this post as the year goes by, but I believe this is a good opportunity to share my most favourite piece I've written for this student magazine (so far) to a wider audience (hopefully) than just the one or two active followers on the Letterboxd (thank you Madeline especially). You can read the original piece on Letterboxd here, but this is a more visually appealing version with accompanying images and links to films for your viewing. This is also a slightly longer version that includes certain texts previously hyperlinked but are now added in full for contextual convenience.

I swear this 37-minute read will be worth it ;)

[Originally published online 28th October, 2024]

As the title suggests, this piece does not intend to be a singular treatise of my own thoughts and opinions on film's predilection to judgement as an art medium (criticism) and as a barometer for lack caused by spatial-temporal-ideological distance against the familiarity of emotional catharsis (nostalgia).

Similar to the way cartographers arbitrate multiple topological elements such as placement of shapes, symbols, language, and their generalisation/reduction for accessible pattern recognition, I attempt to curate the sprawling interpretations and conversations I've had with friends with varying degrees of engagement to cinema—alongside quotes and statements from various filmmakers I believe hold eminent influence in understanding and defining the medium as it exists currently—and through their close proximities and juxtapositions from each other hopefully inspires a basic ideological guide/roadmap towards a more rigorous, subversive and liberating possibility of manifesting filmic expression.

The conversations featured in this piece have been edited and revised for clarity.

Jean-Luc Godard, Scénario du film Passion, 1982.

Your whole career, including your work as a critic, can be seen as a process of negotiating, coming to terms with cinema.

Godard: I don’t make a distinction between directing and criticism. When I began to look at pictures, that was already part of moviemaking. If I go to see the last Hal Hartley picture, that’s part of making a movie, too. There is no difference. I am part of filmmaking and I must continue to look at what is going on. [With] American picture[s], more or less one every year is enough: they are more or less all the same. But it’s a part of seeing this is the world we are living in.

Is filmmaking a utopian activity for you, in a sense?

Godard: The way I wish a movie should be is a utopia, but to make a movie, to make it, is not utopia.

- Interview: Jean-Luc Godard by Gavin Smith for Film Comment, March-April 1996 Issue

8 October 2024

1(a).

Tim Wong, Out of the Mist: An Alternate History of New Zealand Cinema, 2015.

(if you're reading this Sophia, ty for listening in <3)

There used to be a dedicated film publication in New Zealand called The Lumière Reader. It's been defunct since 2016, and most of their writing is not fully archived nor digitally available to view anymore. I guess that's how I view the state of "film criticism" in Aotearoa lol. [Film criticism in Aotearoa] currently has been sidelined towards accelerating actual film production (i.e. Day One Hāpai te Haeata, PASC). It’s good that lots of young peeps are being encouraged to make movies, but I also know that the scope of these initiatives is still pretty disappointing.

There's this long-standing belief that Art = Culture, that art has to maintain certain (liberal/progressive) ideological structures and practices if you ever want it to reach some form of mainstream attention by producers. 'Culture' (at least here in NZ) being one that champions narratives surrounding subjects/identities that fit the globalist multicultural status quo of the industry (movies by women, non-Pākehā) or the more tried and true rep of NZ being a hub for outsourced CGI labour by Hollywood studios. That is the state of movies in New Zealand unfortunately, as much as all the countless puff pieces NZ film critics hired by NZME like to proclaim because that's what their job requires them [to be]. Nation-building cheerleaders. God forbid they give a scathing critique on any aspect outside of the [narrative] filmic world these NZ-based filmmakers like to regurgitate back to us by their "industry mentors".

You already know that I think this is bullshit.

Surely there's more to making movies than just trauma dumping in film festivals and getting brownie points by execs only for them to keep whipping you to make more trauma movies until you bag an Oscar [for them] that the studio will use to increase their rep and hire even more naive filmmakers for more trauma movies. That’s the cruel systemic cycle I see all of my filmmaker friends are hurtling towards. Cinema as [self-submission towards hierarchy], which can be exploited accordingly.

1(b).

Hollis Frampton, Heterodyne, 1967.

I also think about movies that aren't always inspired by anything humanities or fine arts related; something towards the sciences, not the way Nolan does it. I mean genuinely parsing the film as you would intuiting mathematical algorithms and formulae. Math as structure, not as imagistic aesthetics necessarily.

It’s possible.

I began to make [Heterodyne] when I had no money for raw stock and only several rolls of colored leader but nevertheless (had) the need to make or work on a film. As I first conceived the film, I intended it to be a kind of revenge done with the bare hands against - first of all animation - or cell animation in particular and secondly, against abstract film with a capital 'A' as they were practiced in the late 40's and 50's as a kind of engine cooler for the art houses where I first saw serious foreign movies. As I thought about the film, I wanted it to have a very open, resilient kind of structure with the maximum possible amount of rhythmic variety, both in terms of count, beat and variety in the rhythmic changes of shapes and the rate of the rhythmic change.

I used a debased form of matrix algebra to make up, in advance, the structure of the film, and tried out several arithmetic models for that structure... with very short film pieces, before I found one that seemed to suit me. As I came to make the film, it consists entirely of 240 feet of black leader into which are welded about 1,000 separate events. Each consists of one frame, and there are 40 kinds of frame, ranging from a frame that consists entirely of red or green or blue to a frame which may consist of red leader with a triangle of blue leader welded into the middle of it. I say welded because the film was put together using three colors of leader and 3 ticket punches - a square, a circle and a triangle - which I felt to be constantly recognizable and also impersonal shapes - and where one color is let into another, or where a color shape is let into black leader, it is literally welded in with acetone.

I was doing all of this under a magnifying glass with tweezers and brushes and so forth... they're disposed along the continuous line of film by a scheme roughly the following: in order to avoid a scheme in which certain types of frames would, by rhythmic recurrence, fall at the same spot in the film, or in the same exact frame, I decided to use prime numbers, that is, numbers divisible only by themselves and as a starting-point since they begin to share harmonics extensively only in their very high multiples - I further decided I could use no prime numbers less than 40, because 40 is the number of frames in a foot and didn't want any single type of event to occur any more often than once every one and two/thirds seconds, and then I subjected my list series of tests that involved the sums of their digits-casting out those that didn't meet the tests so that as it turned out the commonest event, a frame that is entirely red, occurs every 61 frames in absolutely regular repetition throughout the film; and the least common event, a red triangle on a black ground, occurs every 2,311 frames - all of this necessitated an amount of arithmetic which I did over a period of 6 weeks - reduced it to a large stock of 3X5 cards and collated them, and sat down with my rewinds and splicer and simply put the thing together - altogether on the level of personal logistics, it tied up my time and need to be making a film for about three months at the end of which I found myself with a little more money for raw stock and I could go on and make other kinds of films.

- Hollis Frampton, Notes on Some of Frampton's Films

Abstract art emerging from the most rigid and determined process. That to me is beautiful, liberating, like learning how to ride a bike all over again and experiencing the adrenaline rush of being able to go wherever which way you want. I think the beauty for me lies in how contradictory the experience felt for me [watching Heterodyne for the first time]. The flashes of images "feel" random, but they're not, and I think that's a good synecdoche of how people approach all things in life: How do you make sense of "a series of random events" from the limited perspectives you have? You can find comfort in rationality, in the seeming determinism and inevitability of life, in all things having certain karma, in the ever-entropic expansion of the universe, but will these "patterns of analysis" nourish you in any way on how you feel and exist currently? You can choose any innumerable amount of socks, but you only ever have two shoes. The choice is where meaning emerges. Choosing and creating new patterns, that feeling of discovery is what I feel is missing in movies.

Movies these days are there to remind you of stuff you've experienced before and provide you comfort. Daring to learn and achieving self-awareness is not good for business. You [apparently] have to side with the culture if you want to make it, which is an artificial responsibility put on the filmmaker. Culture does not start in the movies, nor should one govern the other.

1(c).

Andy Warhol, Empire, 1965.

(Refer to Isiah Medina's Towards a Theory of Film Production: Part 1)

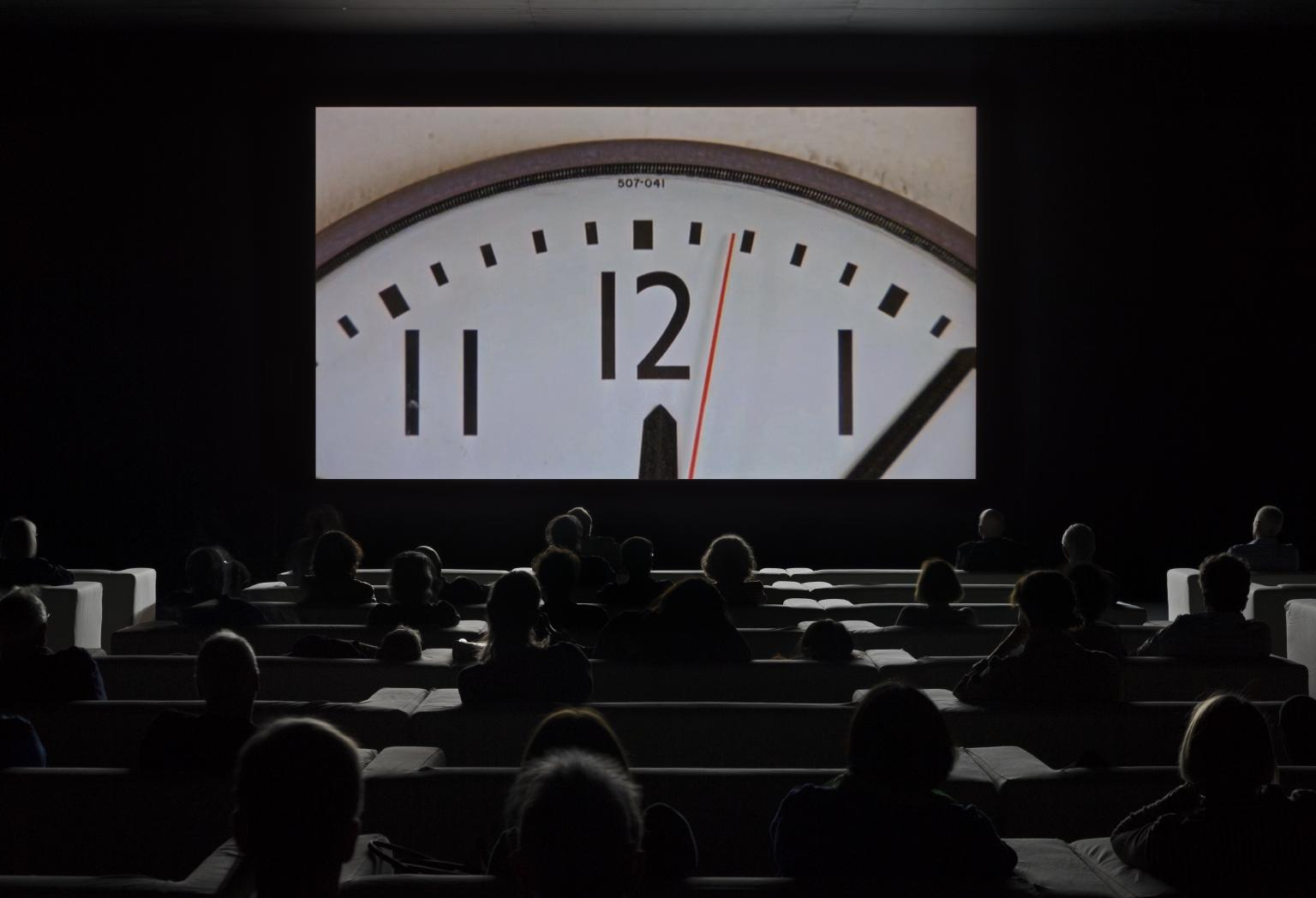

Time-based media is underrated.

There's this movie called The Clock (2010) that is made up of 24 hours of movie clips of clocks that matches the exact time and place of its chosen movie clips with the local time zone the movie happens to be screened at. Or you can be Andy Warhol and stick a camera showing the Empire State Building for 8 hours (Empire, 1965). Or you can be like Phil Solomon and remake that [same] film in the video game world of GTA IV using the in-game day-night cycle (Empire, 2008). The possibilities are endless.

Kelley Dong, Pears, 2020.

They don't even need to have long durations. The specific platform where you view time-based media can also be important. How much info can a second contain, and does one only need to see art once to actually understand it? The fact that [Pears] goes by so fast with so much aesthetic info contained in those two seconds sorta startles your predisposition of "viewing things" that now felt passive [before] since it ‘feels’ that the film ended abruptly. Did you really catch everything, and thus can you base your interpretation on this seemingly 'incomplete' experience of the film? The fact that YouTube can give you the option to autoplay to the next video (or hit rewind and/or choose from the grid of recommended videos) is part of the viewing experience. You are given the choice to replay the film or move on, and hitting replay often involves your next viewing suddenly being hyper-attentive to everything you see in the film from now on.

I guess those are the two ways of experiencing films: repetition vs duration. Do we understand things more if we experience it again, or by experiencing it for a long period of time? I can play a video game for 30 mins a day for ‘x’ amount of days, or I can theoretically stay up and play it for as long as I can until I can longer play it. Who understands the game more?

Isiah Medina, 88:88, 2015.

What’s it like being of Asian descent and making movies where you are?

Medina: A curator once told me I’m not focusing on identity enough, and I find this interesting. By virtue of making 88:88 (2015), I will show you what I am here, but I find I’m often confronted with a claim that I’m not doing it right, or enough, or I’m doing it wrong, within Canada, or even for Americans who watch my pictures, there’s this idea of how I should or shouldn’t represent this or that or it’s seen within the lens of American racial dynamics. And of course I share the English language with Americans, so there’s this double or triple aesthetic struggle. Rather than in-betweenness, it’s subtraction. If I can make an American-looking picture with this idea and this story, and everyone can have their own Griffith, I really don’t think this is an advance. He says he has it in his head, but you don’t really know what’s in your head until it’s externalized, and with him, as soon as it’s externalized, it’s too late, it’s all wrong, whether it’s with aesthetics or his finances. Compare him with the planning and theorization of Eisenstein. Even if it doesn’t work temporally you can say Griffith is Aristotle, and Eisenstein is Plato. Griffith is the manifest image of our cinema, whereas I think Eisenstein goes towards a scientific image that is in battle with the manifest and we get to see this tension. Like philosophy, most conceptual battles are between a Platonic and Aristotelian route. And I think the same is true for cinema, that so much is still a question of Griffith vs. Eisenstein in terms of what we truly value. It really doesn’t make me feel good to see someone who looks like me in an American-type picture if there’s no play with forms. It’s the play with forms that is the place of identification. It’s why I don’t like when people complain how hard it is to make pictures. Maybe if you’re making that type of picture but I wouldn’t know, that’s not what I’m making. I don’t need too much. The fact is, I think making art is fun, it’s joyous, I don’t think it’s this sort of struggle, work ethic, no one is forcing you to make art.

1 October 2024

2.

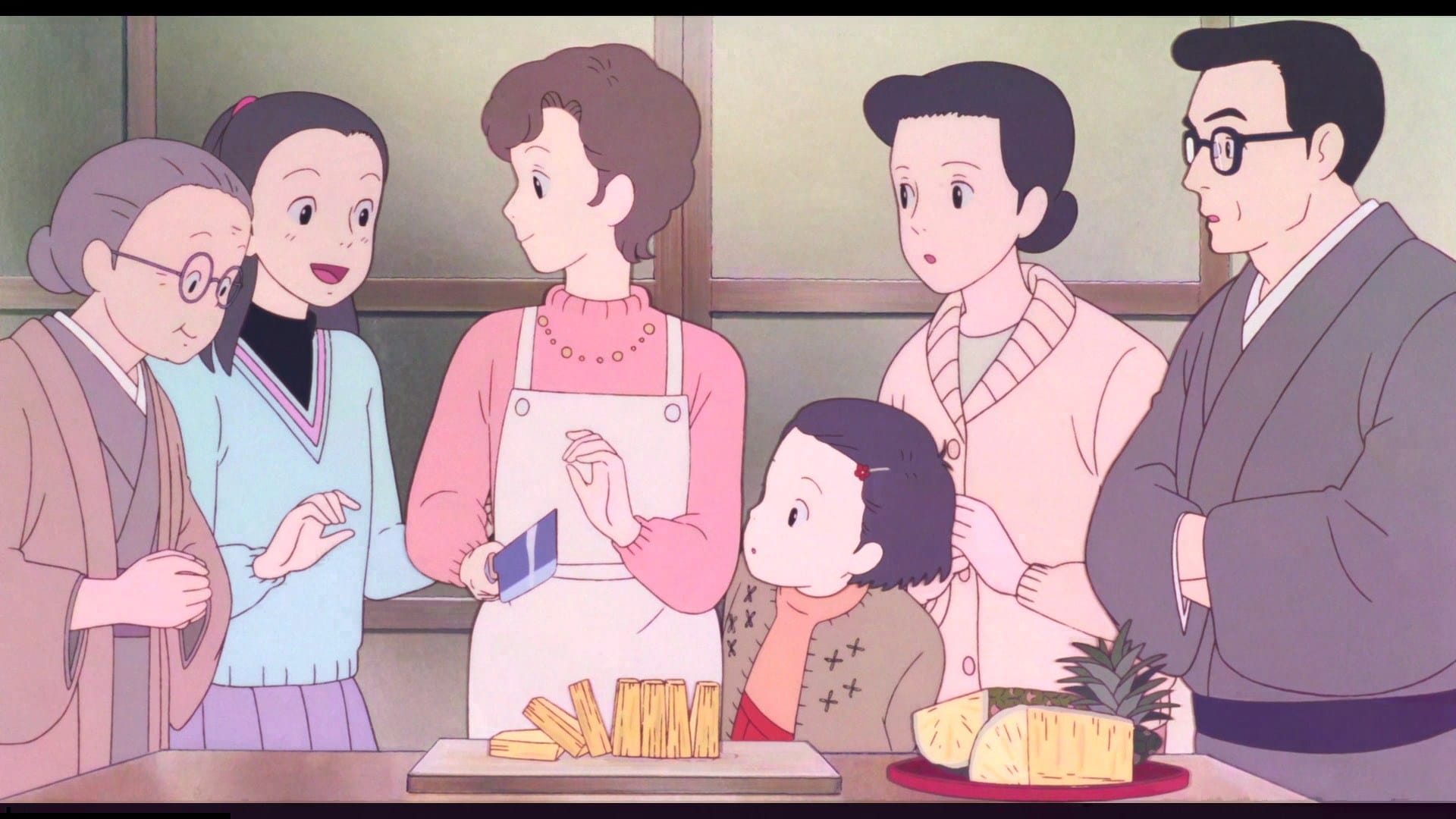

(Refer to Madeline's piece on Isao Takahata's aesthetics of nostalgia)

Trevor Pronoso: Your take on Only Yesterday being a sober mourning of the past as manifesting through 'memory' had me wondering whether or not there exists a certain irony/falseness of Takahata's aesthetics in depicting the 'past' as utopian/Edenic in the first place. Sure, the winds of change can crash down on one's innocent worldview without any respite, but I assume Takahata is more sincere (probably as either a cause and/or effect of Studio Ghibli's targeted audiences mainly children and family, and thus has to be mindful of being tasteful and welcoming in its aesthetics and avoid depicting largely violent/shocking imagery) compared to something more tongue-in-cheek that is conventional in most dominant cinema (I think Howard Hawks, Griffith, the genre of melodrama sometimes, all modern A24 'arthouse' movies), or maybe not? I don't know. Surely there's some delineation between a rose-tinted, tunnel-visioned depiction of the past versus a supposedly Hellenistic 'ethically superior' a priori version of the past that somehow crossed over from theory into reality but has now been shattered? (That latter point being a fairly conservative angle to approach Takahata.)

Madeline Smith: I think you have a very good point about Takahata's vision of the past and how it might not be especially far from the restorative nostalgia that Boym critiques. I've seen quite a few readings of Takahata's work as conservative overall, and while I don't completely agree, I think it's not an unfounded reading. There's an element of social critique in his films, but he uses a conservatively Edenic/utopian view of the past to make that critique. It's a contradiction I find interesting, but it does arguably weaken the effect of his social critiques. I also feel this way about Miyazaki's tendencies for pastoralism. I think both Only Yesterday and Princess Kaguya are masterpieces, but I think Princess Kaguya is the less compelling as a feminist film because it envisions Kaguya as having this perfect childhood before being placed into the social role of a princess. It's written as if childhood is free from the imposition of gender roles and that there's a utopian world 'before the law' (a notion that Judith Butler quite rightfully attacks in Gender Trouble). I think Only Yesterday is much more interesting in this regard because it denies that Edenic view of childhood, and instead shows how it's actually where those roles are most heavily imposed and rigidly enforced, even if Taeko wants to believe there was a perfect past before that. This isn't to say Only Yesterday is perfect as a feminist film (much as I love the ending, the implications of it are quite conservative in this regard), but that I think it's a more sophisticated and reflective view of the past than in his other works.

The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, 1980.

I think the life cycle is all backwards. You should die first, get it out of the way. Then you live for 20 years in an old age home. You get kicked out when you're too young, you get a gold watch, you go to work. You work for 40 years till you're young enough to enjoy your retirement. You go to college, you do drugs, alcohol, you party, you get ready for high school. You go to high school, you go to grade school, you become a kid, you play, you have no responsibilities, you become a little baby, you go back into the womb, you spend your last 9 months floating. You finish off as a gleam in somebody's eye.

- Sean Morey

10-11 September 2023

3(a).

Frank P: I've been really intrigued by the nostalgia/melancholy bait genre of Instagram reels. They're able to capture emotion so precisely with so little time and material, but of course they're also very toxic and reaffirm insecurities that just makes the viewer more obsessed with the idea. I wanna make something that thematically goes beyond that obviously, but I also want to take that moving quality within the imagery and acknowledge the reality and validity of those potent emotions—how in spite of our longing and nostalgia there's a way to move on; and how in spite of being able to move on and be present, there's a way to accept and honour those memories and emotions.

Trevor Pronoso: I like the idea of moving on from nostalgia, but it's also one of those late realisations I've had watching film essayists/materialists like Harun Farocki, Straub-Huillet, and late Godard: you're gonna need that strong sense of historical/cultural "distancing" of the subject not as some sole individual who is given the privilege of being psychologically represented on screen, but as that individual being another cog, another piece of dirt in the mountainous pile of non-linear historical analysis. Kinda like how you never just take a landscape picture of the Sky Tower and only come with the conclusion that the Sky Tower should be the locus of your attention and identification [see footnote]. You have to constantly scrutinise your subject within the real-life material conditions they're in and how other non-visible elements (metaphorical, spiritual, metaphysically impossible elements to represent in film: i.e. the souls of dead people that once inhabited the same space as the subject) contribute to the wider tapestry of its context. It’s why I see Peter Kubelka's cinematic form of neverending juxtapositions between sight and sound and every audiovisual thing that occurs [simultaneously] pretty much giving you all the tools for imagistic interrogation. I’m reminded of your notes on [Hou Hsiao Hsien] and his fixation on consequences rather than climactic moments. To pick up the pieces and suss out the hidden/lost contexts and events that have occurred though your subject is how I’d think one can move on from nostalgia.

Excerpt from lecture held during 25 FPS International Experimental Film and Video Festival, in Zagreb, 2010. Video by Igor Lušić and Daria Blažević.

Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet, Introduction to Arnold Schoenberg’s Accompaniment to a Cinematic Scene, 1973.

Introduction to Arnold Schoenberg’s Accompaniment to a Cinematic Scene (1972) is a good example of this "alternative to nostalgia" at work. One feels initial nostalgia for Shoenberg’s well-renowned piece, and then [is subsequently provided] historical analysis not by playing the piece as intended, but by reframing it within the film's contemporary zeitgeist of the time (1970s). ‘Contemporary zeitgeist’ involves filming an actor reading aloud letters Schoenberg wrote while in exile in America as a Jew in WWII towards a tape recorder inside a [sound-proof] studio, and subsequently bookending the film with an abrupt authorial/formal interjection by Straub-Huillet that highlights the hypocrisy of Schoenberg’s allegiance to American authoritarianism after defecting and being complicit towards the ongoing anti-communist attitudes of the United States spilling over to their involvement in the Vietnam war. The film is [stripped] of its nostalgic, ahistorical, abstract qualities and brought back down to reality. To "acknowledge" the feeling of nostalgia is already inherent in the presence/participation of the viewer to it. "Acknowledging" nostalgia is a redundant act because you need to give the viewer its total opposite, its anti-nostalgic antithesis. It all goes back to constant dialectical clashing, never mind attempting to "honour" those past emotions. Let the viewer decide if those emotions are still worth holding on or not. Don't give the viewer closure and the finality of determinism ("determinism” in the sense of excusing nostalgia of its past mistakes ignoring its present systemic vice grip.) The potency of nostalgia should be a non-factor when you're dealing with the real-life consequences of it, if you want to move on from psychological echo-chambering.

FP: I stand differently to you here. You seem to want to reject nostalgia, rather than accepting it as a natural aspect of our psychology and how it may coexist in harmony with present reality. I'd like to think that we never really truly "move on" from things, and that's ok, and that doesn't mean being trapped in any kind of "vice grip". To reject the potent emotion is just cold and self-deceptive to me. A film that emphasises "anti-nostalgia" is too postmodern for my liking. We can acknowledge the fallacy of nostalgia but also its natural inevitability. We can take both of those and forge a new way of looking at things that doesn't seek to push away any emotions and only enriches the present experience.

TP: Nostalgia is an inherently conservative feeling; it is yearning for a past that favours momentary denial of the present. Maybe I have an absolutist definition of nostalgia, but to take the approach that ‘human behaviours’ such as nostalgia is cyclical only to reluctantly throw one's hands at its "inevitability" is to downplay the entire endeavour of challenging it, of moving on from it in the first place. You might as well call all forms of indigenous decolonisation and ‘deconstruction’ as postmodernist as well because it seemingly rejects a nostalgic unified nationalistic hegemony of society and culture following that through-line. In my eyes, there is no coexistence, only the constant Hegelian struggle towards freedom. Globalist pluralisms and all that stuff reinforce assimilation, reinforce a conservative, ignorant viewpoint that wishes to shove all indigenous difference out the window and join in the amorphous blob that is "human". Nostalgia could be as natural as human aggression, but it doesn't make it any less dangerous.

FP: I'm not sure that decolonisation comparison works for me. Cultural hegemony and etc. needs to be rejected, clearly, similarly with nostalgia. Cold hard logic tells us it needs to be rejected for the same reasons. But you're not acknowledging the purely emotional aspect of it. Indigenous cultures yearn for a present/future free of hegemonic encroaching, that makes perfect sense, it's the natural and harmonious way things should be. But for us individual humans to yearn for a present reality that rejects any sentimentality we inevitably associate with the past is wholly unnatural for our psychology and even hormonal functions. It's anything but harmonious to me. I don't believe in "fighting" emotions the same way we need to fight colonisation. Maybe it's just me, but personally I despise any act that constitutes "self deception". To reject a whole emotion is definitely that. And of course, nostalgia itself is also self-deception. But [nostalgia is] also natural, and it's in not letting it take over, being able to address it, that it becomes a truth—the truth that the nostalgia is there, and that's cool. Whatever amount of deception there is in nostalgia is so much less harmful than the amount of deception it takes to reject all those emotions in my opinion. It's in neither becoming its slave nor completely ignoring nostalgia that I seek a third way to move forward. I definitely don't agree with the absolutist way of thinking. It's right, but unpragmatic when applied to nostalgia. I reckon Hou's Dust in the Wind (1986) is a good representation of the kind of thing I'm currently thinking of.

Eadweard Muybridge, Sallie Gardner at a Gallop, 1878.

TP: Late reply, but this review pretty much sums up my current attitudes towards intuiting "emotion" in cinema:

Sallie Gardner at a Gallop did not invent moving pictures and neither did it introduce the pictorial representation of movement. Proto-filmic mechanisms existed long before it. Muybridge’s real achievement with Sallie lies in a different aspect: The precise acquisition of knowledge through a camera. Muybridge poses a question (Does a horse ever lift all feet off the ground while galloping?) and answers it definitively (yes). Sallie wasn’t created with an audience in mind. Cinema (art, communication) happened only as a byproduct. It wasn’t about beauty, it wasn’t about triggering profound emotional responses, it wasn’t about making didactic bits of communication for others to consume and reflect on. Here the mechanic apparatus is a tool for scientific discovery. “Scientific” films today tend to not have this quality. They don’t use film for scientific discovery; they use it to communicate previously gained scientific conclusions through presentation. The mediums role in these films is distribution of knowledge rather than acquisition of knowledge.

But recently some filmmakers have begun to connect back to the way Muybridge used film. They’ve taken an interest in science and progress.

Now the idea is not to go and start analyzing movements again, the idea is to build a bridge from pre-cinema, (Jannsen, Muybridge, Mulvey) to something beyond cinema. Operating under pre-cinema values, i.e using film as a tool for discovery, but choosing to tackle bigger questions than motion.

Muybridge himself already took the first steps. Look at this film Child bringing bouquet to woman. It’s a motion study, but what is Muybridge trying to gain knowledge about here exactly? It’s not something as clear cut or as material as the question in Sallie. It’s not the existence or absence of a particular pose in time he’s looking for. He’s looking for something beyond motion. There is a metric grid behind them. On what level is Muybridge operating here? Why is he trying to quantify the motion of a child bringing flowers to a woman?

The main difference between Sallie and Bouquet is that in the end the scientific discovery of Sallie can be reduced to one single frame; the frame in which the horse levitates above the ground. A well timed single photograph would have done the job just as well. Film as such wasn’t necessary – but there are questions where film IS necessary. I don't think Bouquet can be reduced to a single frame but it lacks a definitive result like Sallie. In Bouquet there is no precise answer to a question. Or maybe the problem is just that we don’t know the question. Sallie is only a precise acquisition of knowledge because we know the question that it was trying to answer. What question can we ask about Bouquet?

And more importantly, what can we take from it?

To strip the intent of communication, strip audience psychology. Not using editing as a rhetorical device for an argumentative structure or story but as a device for organizing information.

Quarrelling with nostalgia is all fine and dandy, but what you and I both can agree on is the need for this third alternative way of looking past the imagistic conceit. Maybe my trajectory is through pre-filmic means. Hell, maybe it's pure rhetorical argumentative ‘film essays’ that seek to use film as a ‘cultural science’.

FP: Yep. I think it makes every bit of sense, I'm not disagreeing with you. But this stance is just too postmodern and deconstructionist for my liking. Why “strip the intent of communication, strip audience psychology” when those things are inevitably there? If one end of the spectrum is the pure entertainment/indulgence/escapism of studio films and the other end is the type of cinema you describe, why don't we take the power of both to create a third thing that acknowledges the merits and limitations of both and grows beyond them?

TP: I feel like you're misusing terms like postmodernism here. There’s no denial of truth in what I'm doing. Postcolonial/poststructuralism always get lumped up with labels such as that, when evidently they are just critiques of power structures rather than some "objective truth" held by the upper class.

FP: I'm referring to modernism and postmodernism in this context:

1. We recognise oscillation to be the natural order of the world.

2. We must liberate ourselves from the inertia resulting from a century of modernist ideological naivety and the cynical insincerity of its antonymous bastard child.

3. Movement shall henceforth be enabled by way of an oscillation between positions, with diametrically opposed ideas operating like the pulsating polarities of a colossal electric machine, propelling the world into action.

4. We acknowledge the limitations inherent to all movement and experience, and the futility of any attempt to transcend the boundaries set forth therein. The essential incompleteness of a system should necessitate an adherence, not in order to achieve a given end or be slaves to its course, but rather perchance to glimpse by proxy some hidden exteriority. Existence is enriched if we set about our task as if those limits might be exceeded, for such action unfolds the world.

5. All things are caught within the irrevocable slide towards a state of maximum entropic dissemblance. Artistic creation is contingent upon the origination or revelation of difference therein. Affect at its zenith is the unmediated experience of difference in itself. It must be art’s role to explore the promise of its own paradoxical ambition by coaxing excess towards presence.

6. The present is a symptom of the twin birth of immediacy and obsolescence. Today, we are nostalgists as much as we are futurists. The new technology enables the simultaneous experience and enactment of events from a multiplicity of positions. Far from signalling its demise, these emergent networks facilitate the democratisation of history, illuminating the forking paths along which its grand narratives may navigate the here and now.

7. Just as science strives for poetic elegance, artists might assume a quest for truth. All information is grounds for knowledge, whether empirical or aphoristic, no matter its truth-value. We should embrace the scientific-poetic synthesis and informed naivety of a magical realism. Error breeds sense.

8. We propose a pragmatic romanticism unhindered by ideological anchorage. Thus, metamodernism shall be defined as the mercurial condition between and beyond irony and sincerity, naivety and knowingness, relativism and truth, optimism and doubt, in pursuit of a plurality of disparate and elusive horizons. We must go forth and oscillate!

- Luke Turner, Metamodernist Manifesto

And yes it becomes problematic when applied to sociopolitical contexts, which is not what I meant with it. The truth is that cinema has developed into a form of "emotive communication" over the past century. Yes there are limitations to that, but in my opinion to throw everything that "cinema" means to the average person out the door completely when attempting to overcome its limitations is both unpragmatic and in denial of the very legitimate emotional response that we do inevitably get from it.

TP: Which I would think metamodernism would inevitably side with my sentiments because it seeks to challenge that said "truth"? I thought metamodernism was idealistic for that reason; audience emotion of cinema proceeds after its essence after all.

FP: Well exactly, it absolutely acknowledges that, but it also acknowledges the validity of heartfelt sincerity of modernist sentiment. It's a pragmatic idealism to me, and that's pretty cool.

TP: I guess I'm just wondering what such validation of vacillating between "knowledge" and "naivety" is gonna lead you to your third alternative? Metamodernism is just the grand equaliser of human knowledge and experience; a clean slate.

FP: Well it's as the second point says, it's a "cynical insincerity". The way of looking at cinema that you propose takes away the cathartic act of an artist pouring their emotions into their work and letting it emotionally resonate with an audience. What about cinema's functions as therapy/catharsis? Why deny it?

TP: Maybe I’m just trying to give cinema its interminable ego death; no individuality, [just] pure tool for social change. Emotions are already present in the image, but not its end goal.

13 September, 2023

3(b).

Wesley Wang, nothing, except everything., 2023.

TP: Probs a loaded question, but what types of experiences, life events, and or specific contexts you find/have found yourself in that evoke nostalgia, and/or were key memories that are themselves nostalgic? I currently have some vague working theory on this trending hyper-obsession with nostalgia for us Millennial/Gen Z types. Still not confident to share, but I would like to know your input. They can be specific objects, triggers, symbols and the like.

FP: For me, nostalgia revolves exclusively around love and experiences with ex-partners and people I have had romantic feelings for. I can't say I feel particularly nostalgic about anything else.

Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet, The Return of the Prodigal Son - Humiliated, 2003.

[Straub-Huillet] are the guys who have never let me down. I’m a fanatic. They are fanatics. I think it’s the only way to talk about this kind of work. There is no other way of working in cinema or art. Did you see these mysterious shots of wood? It happens two or three times in the film. It’s very strong. When you do things like that, you’re done for the rest of your life. It’s over. You cannot work in this town anymore. You have no more job in this town, in cinema. It’s going very far. Sometimes if there is no reason to do it, you have to go beyond your fear. I tell you, I cannot do it. It’s not a matter of talent. It’s just that I don’t work that much. It’s that simple, there’s no secret here. It’s not a question of being well practiced in the ways of writing scripts, it’s not the number of films that you have seen… It’s life, it’s taking a risk that has nothing to do with cinema. Because we’re not talking about cinema now.

It’s a tension that is very hard to maintain because it’s not in the films, it’s in life. We all know it’s very difficult to be in love all the time. At least, that’s how I feel. I knew Danièle [Huillet] and I was very close to her, perhaps more than to Jean-Marie [Straub], and I know they were in love all the time. I’m not saying that you need to be in love to make art, or to live, to be alive, but it helps. Again, there are things here that you have never seen in your life. It means that they try to keep this tension at the maximum level. It’s very young, very alive, very political, very resilient. All the words you want. But it’s in life, not in cinema. Actually this is one of the least visual of their films, I think. Everything is what it is. Like one of them says, “it’s here, it’s what it is”. So it’s not 'film', it’s something else. The difficult part is not making the film, it’s believing in the film. It’s believing that this is material, that this is more than material, that we can represent it in another way. The strength to believe in going from saying something to doing something. It’s like Ventura trying to get up. You cannot get up nowadays. He can’t get up, because he was seduced, charmed.

- Pedro Costa on the film Umiliati (2003), Diagonal Thoughts, 2 February 2013, Brussels

24-25 July 2023

4.

(Refer to A personal confession on filmmaking after watching Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom)

Trevor Pronoso: I started writing this pretty early in the year, but I held out on it until fairly recently. I was mostly responding to my own observations on the ways I've been writing and thinking about movies for the past year and a half, and I was also reviewing a lot of student short films made by a bunch of young Filipino filmmakers on this Discord server I’m on. Sinegang is a Filipino film publication I've written pieces for in the past and they have a Discord server.

I pretty much need to let film ideas gestate for a pretty long time before I'm convinced of it, lest it sour and rot in its boorish finality. [To me,] editing process > actual shooting process almost all the time. But tl;dr, filmmaking with the primary aim to just film willy-nilly in the name of manifesting your will to do stuff is kinda repulsive, self-absorbed, and irresponsible; get better optics or a sound thesis before you film stuff. I'm tired of seeing film as this "creative playground" and careerist mode of individual expression. Maybe that’s why I'm very weary of ‘filmmaker’ personality types. You're gonna find repeated indulgence of interiority/personal originality pretty repetitive and asinine, lest you start to look outwards in the material world.

Film is a medium of decoupage, not a conjurer of ineffable emotions. it's pretty pretentious to say that the vast spectrum of the human condition/emotions is incomplete and requires art to produce new ones. Every form of emotion felt by humans has already existed and will continue to exist. And film's responsibility is to form meaningful connections within these emotions.

Royco: This piques my interest. What do other (fellow) Filipino filmmakers in this country make films about? There's two other Filipinos I know [who are] in the same degree as me, and for their short films they had a Filipino-oriented story of being a “chocolate marshmallow”, a thin brown veneer hiding a soft, white inside. It’s interesting, but when I found out they both were doing similar topics, my interest deflated.

In layman's terms, what does ‘letting film ideas gestate’ mean? [Until you are] convinced of what, the director/maker's convictions that led them to make the film in the first place? I’m convinced if I make a political film (which I've toiled over for a while), I’d be doing so with the gall thinking my opinion matters. [Yet] the question that gets in the way of everything is "why not?"

But regardless of what is produced, it should simply be judged by the merits of the art or work itself. The fluff behind the scenes means nothing. The dynamics between a head chef and a sous chef means nothing to a customer who only cares about what they ordered. This leans into the "separating art from the artist" train of thought I guess.

Film should be a creative playground—like you said it's a medium. Mediums are for anything and everything to pass through it, and usually a lot of junk films under the belt of a director means they're cutting their teeth and becoming skilled as time goes on (optimistically speaking). In this world full of utter suffering and pestilence, what people of lesser creative will should [at least] get—especially if they're actually determined to do it—is decadence and indulgence in their journey to professionalism. there's a market for everything anyway.

What irks me about your view of ‘pretentiousness’ is the assumption that filmmakers knowingly go into projects with a degree of pretentiousness. Would it also not be pretentious to want to define that whole medium's responsibility? We're all pretentious in the film industry. It just is what it is, and I will sleep happily knowing that I am (at least) presumptuous on what people may feel and why I think they should watch what I make or something like that.

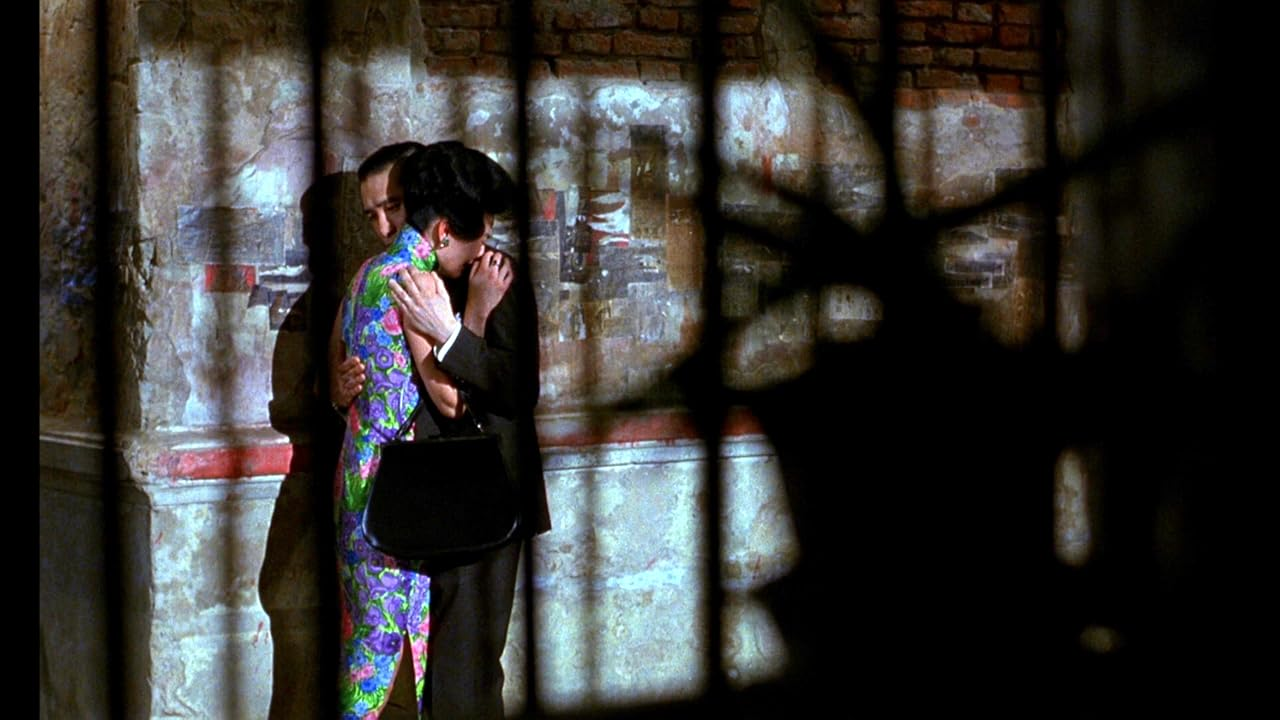

TP: At least from the Filipino short films available on their Discord, I'd say most of these films have got a strong anti-Marcos political edge (who woulda thunk lmao) There are lots of COVID/pandemic films (Sinegang was founded during lockdown) and lots of very arthouse Wong Kar-wai adjacent types as well. I wrote a review for one of the short films, which sounds very similar to our discussions about filmmaking philosophy/process.

I've also had another discussion with a friend about why some of our favourite filmmakers like to do shit on the spot during production/shooting, especially in relation to Wong Kar-wai. I think this new generation of filmmakers are drawn to WKW for the nostalgic aesthetic and free-association filmmaking process. I countered that people adopting a similar WKW/nostalgic style are being intellectually dishonest/very lazy considering the low conceptual effort and emphasis on ephemerality equating to cinematic/poetic flourish. It’s a low barrier of entry, and the results can vary person to person, which then creates a terrible expectation that one's filmic success/poetic effectiveness stems from an essential trait of the individual, that my film pales in comparison to WKW because I don't have that ‘X’ factor/artist's temperament/abstract uniqueness. To prop up films/filmmakers within the realm of an inexplicable canon is elitist as fuck.

That’s why I don't want my films to "sour", to feel like a distant memory that can’t be changed/recontextualised for the better, to treat film like a time capsule. It feels "boorish" because I don’t have the power to turn back time and remake a film. It rots in its "finality", in its unchanged static nature. Whether that's some irrational artist's anxiety or the obsessive autistic talking, If I can rewatch my films knowing that I put the most amount of effort that I can during that moment in time. I would feel content.

No nostalgia, no cinema as self-affirmation. Just pure investigation and aesthetic/historical exploration.

Your sentiment on judging ‘art for its own merits’ sounds like wilful, ahistorical ignorance. Cinema is more than what's in frame. It doesn't exist in a vacuum, as pure aesthetics. Cinema is inspired by everything around it. Don't be conditioned into thinking that the customer is always right. Cinema is more than a product for pleasurable consumption. Sure, film is a "creative playground" and I agree with everything passing through film as medium, but when the only thing that passes through is yourself and only how you'd want to present yourself, then you're trapped in an ouroboros of ever-expanding narcissism. Shitty and piss-poor filmmakers deserving professional decadence is bullshit status-quo maintaining nonsense. Don’t be afraid to flip off people for what you believe in. A "market for everything" does not mean "equal distribution of knowledge and culture". Indulgence shutting down your critical thinking skills is deliberate for a reason.

I feel we've got different definitions of pretentiousness. Maybe I should've said "pretentious expectations" towards oneself as a filmmaker and one's "initial reaction" to a piece of art. If so, then you’re correct: it’s pretentious to expect that you can make it in the film industry, to expect that my opinions on the film should be the same for everyone. I mean, if you think I should devalue and write off my thinking on cinema as "pretentious" just because other people aren't putting in the same effort to think more critically of this art form/profession, you can do that. Everythings pretentious then, no meaning. You don't come into cinema thinking your perspective has no meaning and will probably not have any tangible change on the viewer who's watching it. That’s too nihilistic. There are those who are curious, and those who aren't.

It would be nice to have at least a bit of faith that the person making a film knows what the fuck they’re doing and actually puts in a fair amount of effort to offer something subversive, something they know should be taken seriously outside conventional expectations. But we'd rather coddle the viewer in making sure they’re given information and artistic expression with mass appeal, something claiming to have substance only to be hollowed out in production.

Royco: They’re not wrong with your review being harsh, but I don't care as long as it's in good faith, and the main points are there. I propose to you that the imitators of WKW aren't intellectual, they're running purely on aesthetics first. That's what I run on because I'm a student of film's mechanical aspect and an admirer of its technical side. Philosophy has never been a priority in filmmaking for me. It's probably why I work better (for now) as a piston in the filmmaking engine.

Blissful, unintentional ignorance. The good heart and intent lies within what you see as dishonesty at an intellectual level, and it's why I can’t lay a label on someone unless I know for a fact they're hollow. In your experience, has it often been a filmmaker's point to aspire to be their ‘hero’, or is it just admiration and imitation? In that case, the ‘X’ factor would be irrelevant.

TP: It’s a very fine line between aspiration and imitation.

Royco: I've harboured the feeling that nostalgia is poison in a world seeking to move forward. It has never been more potent today than in politics. A film running on nostalgia is nice to a certain extent. I appreciate historical accuracy, in period recreations for example, but it leaves the answer to the question of ‘resurrecting the past’ pretty thin. Take Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood (2019). While I adored the technical and historical attentiveness, the film is a boomer trip and he says so himself.

What examples of ‘historical exploration’ films do you know? I've had an idea of resurrecting 1960s New Zealand for a music video dealing with repressed homosexuality. It’s a mix of nostalgia and education because NZ history is largely ignored in favour of American historicism. I describe it as ‘nostalgic’ because "oh wow it's so long ago!" (despite the prospective audience being born at least 40 years after), and ‘educational’ because "so that's what it was like then." Admittedly a thin reason to make it, but it's only a music video. The soul of the short lies in the song around it.

This is an ask, but can you expand on my view on judging art by its own merits? How is it ‘ahistorical’? I’m just slowly realising how, if this was a discussion on music, I’d sound like you.

Harun Farocki, Workers Leaving the Factory, 1995.

TP: Harun Farocki’s Workers Leaving the Factory (1995) is a good example of this ‘historical exploration’ via a shared (re)presentation of a filmed subject.

There is no such thing as looking at "an artwork in itself". You can choose to look at an artwork in isolation, but you're ignoring pretty much every other form of interpretation as irrelevant. You’re deliberately choosing to suppress meaning. You can be oblivious to meaning, but to remain oblivious is a choice.

Royco: At this stage, I don't take cinema seriously (in a philosophical or business way). I either like a film or I don't, and with both judgments I [try to] consider why I feel that way. Again, it's hard for me to see others as narcissists if they don't even know what they're doing is narcissistic, intentions must come first.

Cinema's purpose lies with the filmmaker or critic. Cinema can exist as purely aesthetic despite the influences pressing against it, sometimes that is the point. The ‘chef versus the customer’ thing, that's me with music. I’m far from a caterer of commercial interests, but I see a balance between the customer and the creator in the product being made.

Too much creator = narcissism? Too many customers = selling out?

I agree [with you] that the creator should carry themselves with their beliefs. I'm just making the point that indulgence isn't a sin during development of one's self. Great creators have shit work, and if there's people who want to lap it up then that's for them to consume it. People have the choice to consume whatever they want and it should be left that way, whether it be trash or treasure.

I just don't hold convictions when it comes to film (different story with music, but not as serious as you are with film.) Whether it's you and your writings or someone's attempt at a WKW reboot, I don't see any of the two as pretentious. I see both as a will or testament to that person's belief being laid out for an audience. There's no elevation of one over the other.

TP: "Cinema's purpose lies with the filmmaker or critic." You’re not really saying anything with that. Of course it is. Instead, you're implying that people do nothing and remain in their own circles, their own markets of cinema consumption just because you don't like one interpretation over another.

Royco: I don't really care about other interpretations. That’s where a narcissism of mine lies. I'd much prefer to just leave things alone and see what happens creatively, within the parameters of that person's beliefs, convictions, principles etc. as a filmmaker. That's their thing, not mine. I don't know about film circles or markets. It’s a “you like it or you don't” for me.

See, I'm with you on films being ‘hollowed’ out, but I can't say I have the guts to really understand and execute it with force. I can tell you "oh yeah I agree, films shouldn't be shit," but then loiter around [mentioning] all-encompassing specifics. I hate the idea of coddling to the viewer but I'm a lot more like them than I am with a filmmaker. Again, with music it's a totally different story. I actually feel responsible in making sure what I put out there isn't vapid, but I'm still cutting my teeth in film.

In a personal sense, yes. I am ‘deliberately choosing to suppress meaning,’ not because I'm stubborn to meaning and don't want to learn the meaning. My attention is just firmly on the icing rather than the filling. It's probably not how one should be consuming film anyhow.

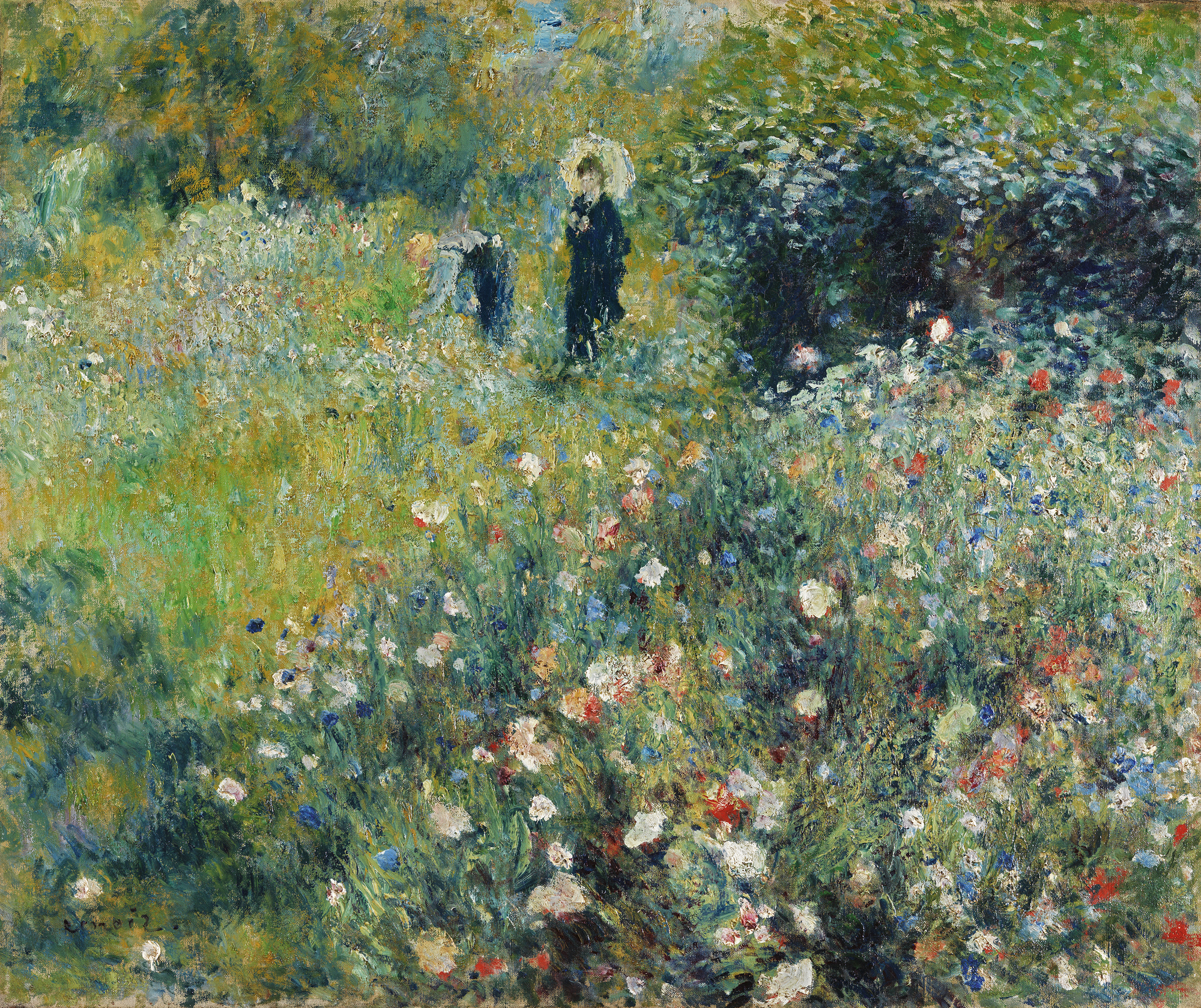

Distribution is not separate, but part of the form of film. And like any part of the form, distribution must be controlled, the same way the artist controls the light, the cutting, the writing, the performances, the camera movements, and the like.

For Pierre-Auguste Renoir, without paint tubes there would be no Impressionism. We can talk about paint tubes and not having to grind your own colours, not having to be an apprentice to a master. We can also talk about YouTube which means free tutorials, immanently large parts of the canon viewable for free, unlisted links of finished or unfinished films to share—and to leak.

But for things to be truly infinite, they must come to an end. Without the figure of the end, we are within the finitude of an opening. Things are infinite because they close. Freedom is to open and close at will.

- Isiah Medina, From Paint Tube to YouTube, 1st September, 2022

Footnote:

夜枭 (Owls See Light, but Not Colour), 2023.

In 2023, I made a short film titled 夜枭 (Owls See Light, but Not Colour) for one of my film courses. The 'picture of the Sky Tower' I am referring to comes from the final minutes of the film, which feature still photographs of Auckland's Sky Tower taken from the corner of Symonds Street and Wellesley Street East. Simultaneously, voice-overs are heard reciting two Chinese poems: 'Nostalgia' by Yu Guangzhong and 'Remembering My Brothers From Shandong on September 9th' by Wang Wei. The recorded audio tracks were slowed down and lines recited from each poem alternate between each other.

Inspired by Walter Benjamin's On the Concept of History, the film's form intends to treat each and every visual and aural material combined and juxtaposed as belonging to the wider 'constellation of tensions' of experiencing historical development in the 'present' as opposed to a linear perspective of historical events dictated by causality. A still landscape photograph of the Sky Tower may feature other existing elements surrounding it such as commercial buildings, construction sites, passersby on a sidewalk, tertiary education buildings, or moving automobiles. These elements that have their own historical subtext recontextualise the pictorial, beatifying qualities of the Sky Tower as inhabiting a diverse, and non-monolithic discourse surrounding New Zealand identity, contemporary Chinese immigrant culture, and the intersections between global commerce and architecture.