Review: THERAPY at The Basement

A musical comedy performance at The Basement Theatre showing between 8th - 12th July 2025. THERAPY was awarded the New Zealand Fringe Touring Award (2024).

A musical comedy performance at The Basement Theatre showing between 8th - 12th July 2025. THERAPY was awarded the New Zealand Fringe Touring Award (2024).

James Gunn’s Superman reboot tries to go bold but lands flat. With awkward jokes, confusing world-building, and forced emotional arcs, it's hard to care – except maybe about Krypto the dog. A few fun moments saved it, but overall, Super... meh.

Sparks fly when TikTok meets Folk Tale in rural North Macedonia.

A review of the Auckland Writers Festival 2025 events.

I asked Eda & Brian a few questions about their time as Craccum's Co-Editors for 2021, and asked them for a bit of advice they'd pass on to future Editors as well.

Review of Child of Dust Documentary (Dir. Weronika Mliczewska). Doc Edge 2025 Craccum Coverage.

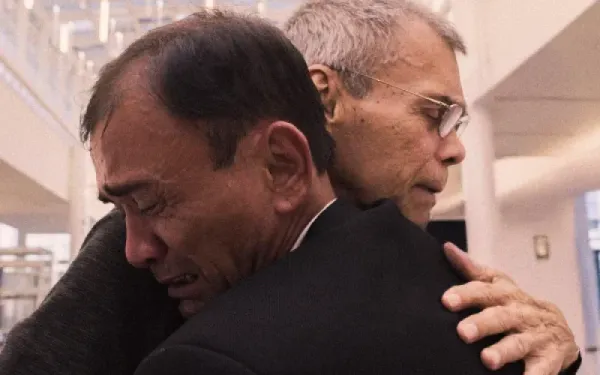

I asked Cameron & Dan a few questions about their time as Craccum's Editors in 2020, and asked them for a bit of advice they'd pass on to future Editors as well.

Auckland Museum’s latest exhibition, Diva, celebrates icons from Whitney to Björk, exploring 400 years of diva history. Direct from London’s V&A, this bold, moving showcase reclaims diva as a symbol of empowerment. With 280 dazzling pieces, it’s a must-see.

Colonised, abandoned, and silenced, The Promise shatters the myth of progress and exposes the price of forgotten liberation struggles.

In seas claimed by giants, Filipino fishermen and soldiers fight not for glory, but survival—abandoned, resilient, and tragically expendable.

Black Faggot is an award-winning play written by Victor Roger in 2013. The show has returned to Auckland, on stage at Q Theatre until 29 June.

Devotional art(washing) at its propagandistic nadir.